Editing Dickens's Working Notes

How to cite this page (MLA): Gibson, Anna and Adam Grener. “Editing Dickens’s Working Notes.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/about/editing-the-notes/

Editorial Methodology

The DDNP aims to cultivate appreciation of the complex and dynamic relationship between Dickens’s Working Notes and his completed novels. This aim emerges from our recognition of the material richness of the Notes, as we have encountered them in their archival setting. While the DDNP cannot replicate the materiality of the Notes, our methodology leverages the digital environment to translate the materiality of the Working Notes into an encounter online (for more information about Dickens’s manuscripts, see the General Introduction).

The DDNP’s presentation of each set of Working Notes—our transcriptions, as well as our annotations and scholarly introductions—is the result of extensive archival research. Our attention to the manuscript pages of the Working Notes is supported by careful comparative analysis of the manuscripts and corrected proofs of the novels they accompany.

Our transcriptions are digital translations—of handwriting into typeset text, of paper and ink into image—that require decisions about how to capture and communicate material facets of the Notes. We have developed and followed a consistent set of principles across all of our transcriptions, and detail the rationale behind those decisions on this page.

A member of the DDNP project team is the lead author for the annotations and critical introduction that accompany each set of transcribed Working Notes. All material, though, has been subjected to editorial review by other members of the team and is thus the result of shared insights, scholarly conversation, and collaboration. Although our annotation practices follow a shared philosophy, each set of annotations develop distinct insights and interpretations. This is the consequence not only of the particularities of each novel and Dickens’s changing use of the Working Notes over time, but also of our different sensibilities as readers and scholars of Dickens’s works.

Transcribing the Working Notes

In almost all instances, our text transcriptions agree with Harry Stone’s, although there are some instances (indicated in annotations) where we offer minor corrections or where our rendering of capitalization or punctuation differs from Stone’s. There are also places where we cannot confirm his more speculative interpretations of deleted text; here, we present the deletions as they appear on the page, simply as non-textual markings.

Transcribing Dickens’s Working Notes as a combination of typographical text and digitally rendered non-textual markings involves a number of editorial decisions.

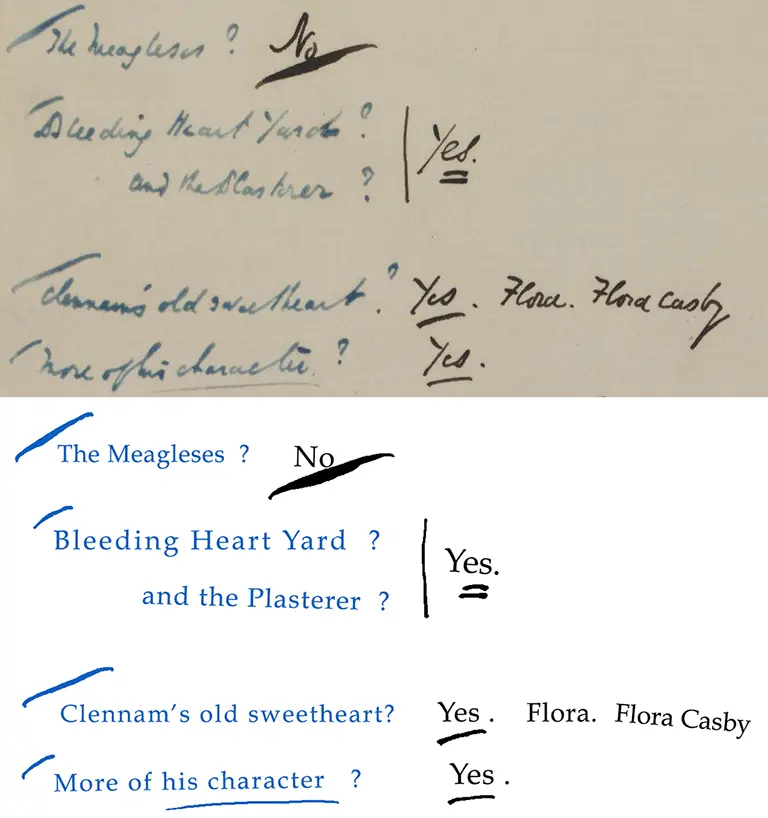

Ink Colors

The vagaries of ink color are the most difficult aspect of the Working Notes to transcribe. Dickens used many types of black and blue ink throughout his career, and often several different inks within the composition of a given number. A comparison of Dickens’s ink use with biographical records indicates that changes in ink were often related to changes in Dickens’s routine; for example, he often used a different ink or pen while traveling. In some instances, oxidation has rendered Dickens’s black iron-gall ink a brownish color. In other instances, the Notes are rendered in various shades of blue ink.

Our transcriptions render the most obvious changes in ink color—for example, a change between blue and black ink on one page—but do not attempt to translate more subtle differences. While such differences in ink weight or shade are visible on the Notes and can provide evidence of distinct layers, they do not offer sufficient evidence on their own, since they may be the result of changes to the quill or the cut of the nib; redipping in ink; variations in ink flow or in the pressure, speed, or angle of writing; and subsequent corrosion of the ink due to oxidation over time.

Where subtle changes in ink color or density inform our interpretation of the Notes’ temporality, those changes are indicated in our annotations, but not in the transcriptions.

For a more detailed analysis of Dickens’s use of inks and the consistency and progression of density and corrosion, see Tony Laing’s in-depth explanation (18-23).

Capitalization and Superscript

The uniformity of typeset text cannot replicate the irregularities of the written hand, but our transcriptions attempt to capture the variability of Dickens’s writing on individual pages.

Dickens’s handwriting often renders certain letters—particularly C, A, W, P, and O—as indeterminately upper or lower case. At times, for instance, an initial C may appear to be larger than the proceeding letters in the word, whereas in other instances the height of the C appears consistent with that of the following lowercase letters (for instance, in Dickens’s varying depiction of the initial C in “chapter”). Deciding how to render these in text transcriptions is complicated by the need to choose between one of two case sizes, a decision that was undoubtedly challenging for Dickens’s typesetters. While the typesetters could rely upon context and convention for the publication of a text for a public readership, Dickens’s Working Notes were intended only for personal use, so our editorial decisions are based on both context and our assessment of the relative size of the surrounding letters. Here are the practices we follow:

- Proper Names — Proper names of characters are rendered with an initial uppercase capital letter (e.g., Arthur Clennam) even when the A, C, or W might be interpreted as lowercase. Other proper names of places (e.g., “Tom-all-Alone’s”) are rendered according to our best approximation of the relative size of Dickens’s handwriting, even though the typesetters regularized the capitalization.

-

Chapter Headings — Dickens is very inconsistent with his capitalization of “Chapter” in his chapter headings. In most cases, the initial “c” is shorter than the ascender of the following “h,” making most of these appear to be lowercase letters. However, since some instances do appear to be larger, we have largely followed Stone’s practice of capitalizing these, except where the difference seemed too arbitrary.

-

Chapter Titles — Chapter titles are rendered according to our best approximation of the hand. Because Dickens occasionally configured letters that have very different upper and lower cases, even in handwriting (e.g. “D/d” and “B/b”), as lowercase in chapter titles, we can assume that he was somewhat inconsistent with his capitalization of titles.

-

Abbreviations — In some cases, Dickens’s positioning of letters in abbreviations (e.g. Mrs, Miss, Dr, qy) might tempt us to render all but the first letter as superscript (a practice adopted by Harry Stone), but unless all letters but the first are clearly raised and significantly smaller than the initial letter, we have used font size to render this difference.

Non-textual markings

At the heart of our transcription approach is a faithful rendering of all non-textual markings on these manuscripts, since these dashes, lines, emphases, and deletions offer unique insights into the function and use of these pages. Our transcriptions render all legible handwriting as typewritten text, but we have carefully reconstructed the pixels of all additional ink markings on the pages. The most common instances of non-textual markings include:

-

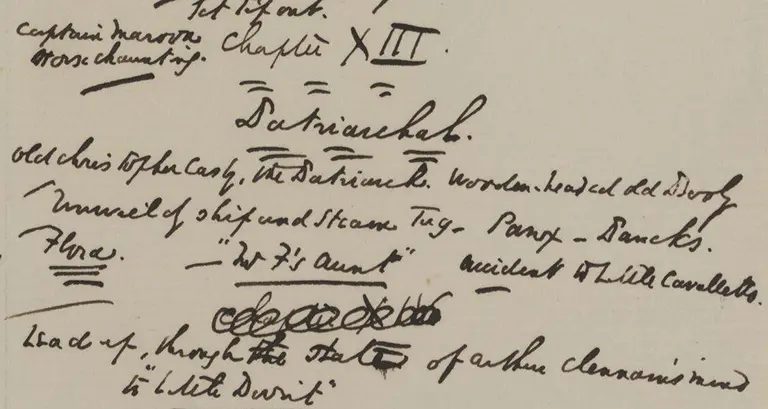

Diagonal lines — Dickens uses diagonal slashes throughout the Notes, often to separate entries that pertain to different topics, plot elements, or ideas. In most instances, these lines rise from the lower left to the upper right. They vary in length, but are often short enough that they become difficult to distinguish from em-dashes, and in certain instances they could be interpreted as underlinings, since Dickens often underlined words at a slight angle.

-

Underlinings — Dickens usually underlines chapter headings and titles, often with a set of three double strokes. In other cases he uses underlining for emphasis.

-

Miscellaneous markings — These include lines that connect entries across space on the page; lines used to separate text associated with one chapter when it runs down into another chapter’s allocated space; accidental marks, such as ink blots; and other unidentifiable markings. In some cases, we have rendered in Dickens’s hand marks that could be interpreted as text, but are too illegible to transcribe with certainty.

Deletions

The Working Notes occasionally contain deletions, where Dickens has crossed through a word or words, usually with a looped line or, less frequently, with cross-hatching. These deletions, however, appear much more frequently in the manuscripts themselves, and so deleted text is not a prominent feature of the Working Notes.

The DDNP transcriptions capture these deletions. Where the deleted word is illegible or indecipherable, no attempt is made to capture the writing beneath. Where deleted words are legible they have been transcribed, and the deletion itself has been captured but rendered partially transparent so that the text beneath can be read. In most instances, our transcription of deleted words match those of Harry Stone, although there are a number of instances where we cannot confirm his text transcriptions of deleted words that we feel are speculative.

Novel and Number Plan Headings

In order to offer a visual representation of Dickens’s handwriting and to demonstrate the relationship between our textual transcriptions and the manuscript text, we have rendered the novel and number plan heading in the top-right as it appears in the manuscript, in an approximation of Dickens’s hand.

Transcription Process

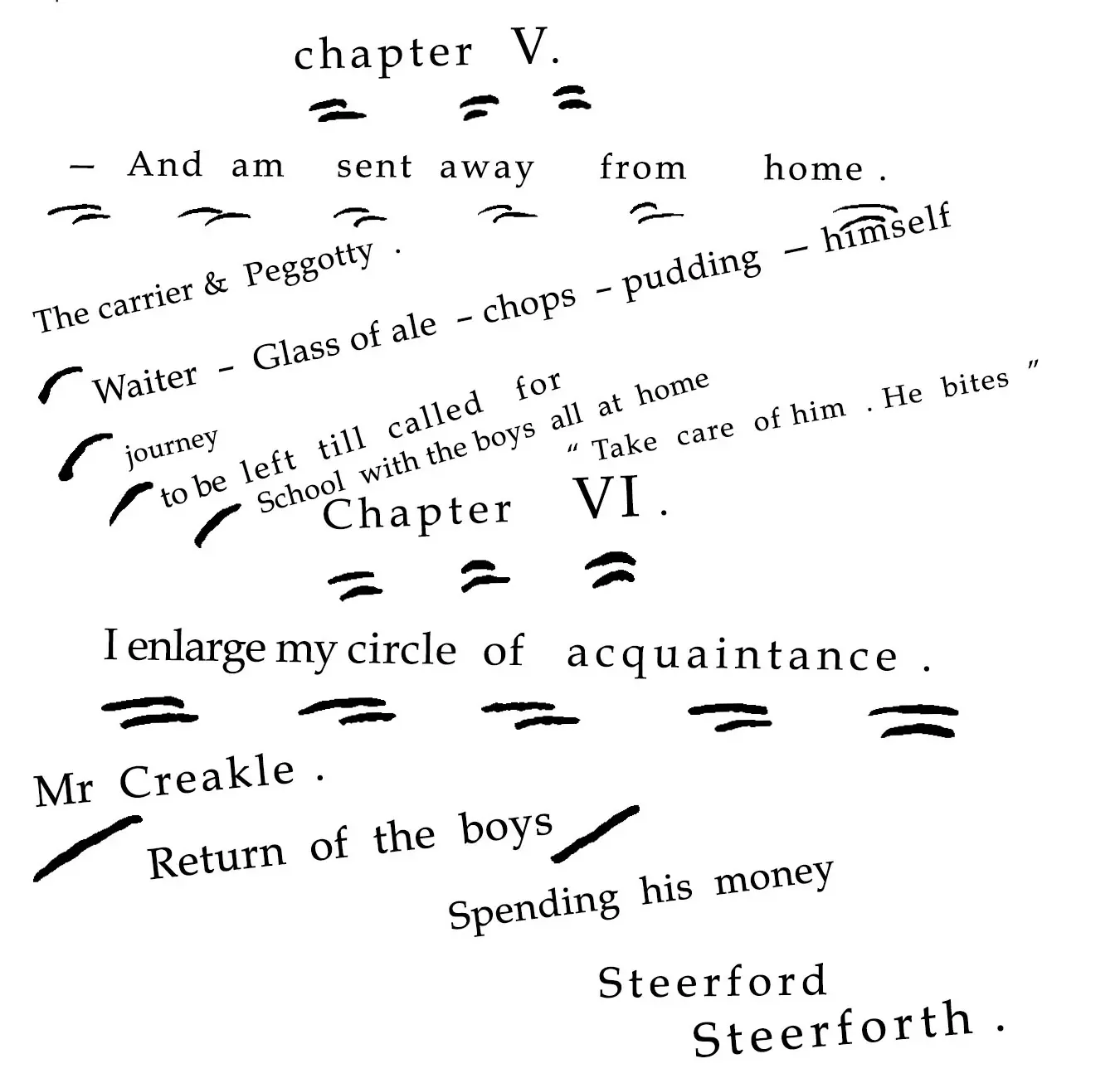

The DDNP presents transcriptions of each sheet of Working Notes as a single image in order to capture Dickens’s use of these pages in the process of composition. In translating the materiality of the Working Note into a digital image, our transcriptions aim to make the text of each Working Note clearly legible while also communicating the spatial and visual properties of the Working Notes.

Transcriptions are created in Adobe Photoshop and generally comprise two layers. The first layer captures the text of the Note. This text, once transcribed, is placed on the page so as to resemble its size and location on the Working Note. Dickens’s handwriting across the Working Notes is inconsistent, both in terms of the size of individual words and also the size of letters within single words. An exaggerated capital letter at the start of a word, for example, or a particularly elaborate descender in a letter (e.g., g, j, p, q, y) can distort the perceived size of a given word.

Dickens’s handwriting is similarly inconsistent in its width across the Working Notes; this is the consequence both of the irregularities of his hand and of the spatial properties of the Notes themselves, as words are frequently compressed into the space allotted to a given chapter or the margins of the sheet itself. While adjustments to font size and kerning (the space between letters) offers flexibility, the regularity of typographical text cannot replicate the irregularities of handwriting. Our transcriptions, therefore, adjust size and kerning to approximate the average size of a word or phrase on the Working Notes. Likewise, the placement of text on the page at an angle or slope aims to capture these variations in Dickens’s handwriting on individual Notes.

Dickens’s handwriting across the Working Notes is consistently far more legible than in the manuscript pages themselves, but at times the writing on particular sheets (or places within sheets) can appear visibly more sloppy or rushed. These variations cannot be captured typographically, but can be identified in editorial annotations.

The second layer of the transcription comprises its non-textual markings: underlines, checks, lines of emphasis, and other non-typographical marks. These marks are hand-drawn and again aim to capture their size and placement on the page of Notes. Dickens’s dashes are particularly inconsistent, both in terms of length and vertical placement (some might be interpreted as underscores). However, in the interests of legibility and consistency, these have been rendered in type as en-dashes in the font size of surrounding text. Similarly, Dickens’s question marks and even full-stops display interesting variations, but have been rendered uniformly in type for clarity.

Annotating the Working Notes

The DDNP’s annotations aim to draw out and illustrate Dickens’s complex and irregular use of the Working Notes. They do so by attending to the material richness of the manuscript pages in their archival settings, and by interpreting the Working Notes alongside the manuscript, the corrected proofs, and the final published text of the novel, as well as other paratextual material—such as letters and biographical information—that might shed light on Dickens’s compositional process.

As our Scholarly Introduction explains, the DDNP foregrounds process in reading and analyzing Dickens’s serial form. Our annotations of the Working Notes are guided by this methodological commitment, but they attend to many different facets of the processural nature of serial form.

-

Some annotations are primarily descriptive and explicate features of the Working Note that may only be legible in their archival setting, such as when a different in ink or nib might indicate a distinct engagement with the note by Dickens (e.g., a reply to a query that is clearly made at a later time).

-

Other annotations interpret the content of the Working Notes alongside the manuscript or corrected proofs. For example, some annotations describe how a name or phrase that appears on the Working Note is actually something Dickens arrives at through drafting and revision in the manuscript itself; this would suggest that the note is a record of a decision made in the process of composition, rather than a decision that preceded composition.

-

Some annotations anchor a given serial installment in its moment of production by, for instance, providing relevant biographical information about Dickens’s movements or activities during a given period of composition.

-

Finally, some annotations interpret the Working Notes within the context of the novel as a whole, identifying patterns that suggest Dickens’s particular attention to a group of characters or plot thread, or interpreting notes as evidence of developments that Dickens considered or rejected.

While each set of annotations is governed by consistent scholarly practices, they do not attempt to offer definitive interpretations of the significance of the Working Notes themselves. Rather, the descriptive, editorial, and interpretive commentary provided by the DDNP’s annotations provides users with new ways to access and explore Dickens’s compositional process and serial novels.

Project Version History

Version 1.0 was released in December 2022 with the Working Note transcriptions for Bleak House and David Copperfield; a critical introduction and editorial annotations for the Bleak House Working Notes; and complete website content, including general and scholarly introductions.

Version 1.1 was released in February 2023. Additions included the critical introduction to, and editorial annotations for, the David Copperfield Working Notes.

Version 1.2 was released in November 2023. Transcriptions, critical introductions, and editorial annotations of the Working Notes for Hard Times and Little Dorrit were added.

Works Cited

- Laing, Tony. Dickens’s Working Notes for Dombey and Son. Open Book Publishers, 2017.

- Stone, Harry. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.