General Introduction: Dickens and Serial Form

How to cite this page (MLA): Gibson, Anna, Adam Grener, and Frankie Goodenough. “General Introduction: Dickens and Serial Form.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/introduction/general/

Dickens as Serial Novelist

Charles Dickens’s career as a novelist is inextricable from serial form. When Dickens began writing his first novel The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club in 1836, he was a twenty-four-year-old Parliamentary reporter who had managed to launch his writing career through short sketches of London life. While the initial monthly installments of Pickwick sold a mere four hundred copies, by the end of the novel’s serial run in 1837, nearly forty thousand copies of each installment were being sold.

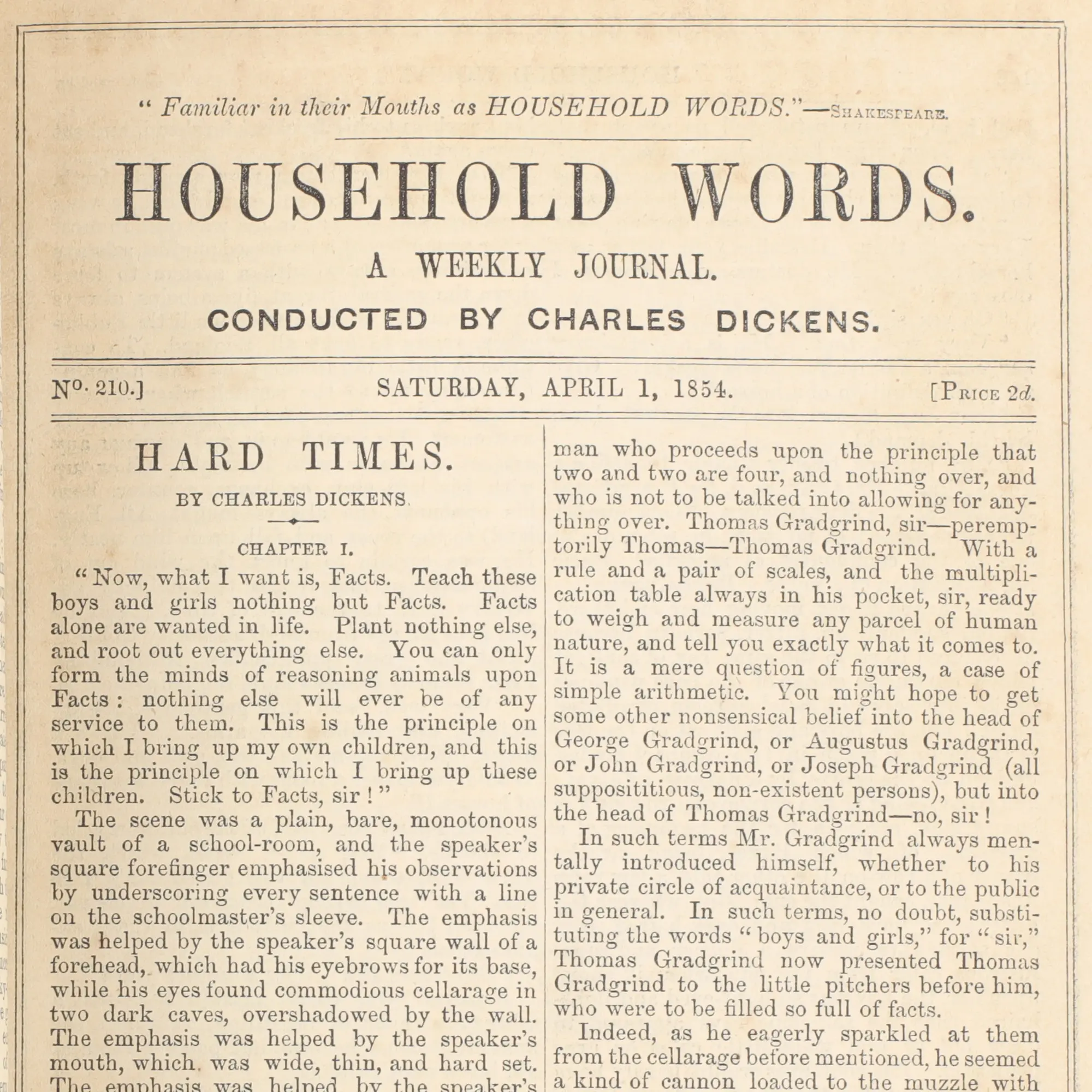

Dickens’s subsequent novels built on and consolidated this success, and their serial publication shaped Dickens’s relationship and popularity with his Victorian audience. Although some of his novels were published in weekly installments in magazines that Dickens himself edited (such as Hard Times, which ran in Household Words from April to August 1854), most of his major novels were published in twenty installments that cost one-shilling and appeared monthly in their iconic blue-green covers (with the last installment being a double number).

Although many readers encounter Dickens through paperback editions that indicate the division of the novel’s chapters into their monthly installments (usually 3-4 chapters per monthly number), it is difficult for contemporary readers to imagine reading and experiencing a novel unfolding in short installments, month-to-month, over the course of a year-and-a-half. It is perhaps even more difficult for us to imagine how seriality shaped Dickens’s creative practice, as he conceived, composed, and published his novels in these installments that were frequently finished on tight deadlines, shortly before they were published and read. The Working Notes he began keeping, therefore, provide unique insight into the dynamics of his compositional practice and open up new ways of interpreting the process of their serial development.

What are the Working Notes?

Dickens began the practice of keeping complete sets of Working Notes for his novels in 1846 as he began to write Dombey and Son. These pages served as records of Dickens’s composition over the course of up to 19 months of serial writing and publication. He used the Notes to plan each installment and track storylines across multiple numbers, but he also returned to the pages multiple times before, during, and after the writing of a number. He used them, among other things, to conceive, consider, question, decide, document, prompt, and remember. These vital records of compositional practice demonstrate Victorian serial novel form in process.

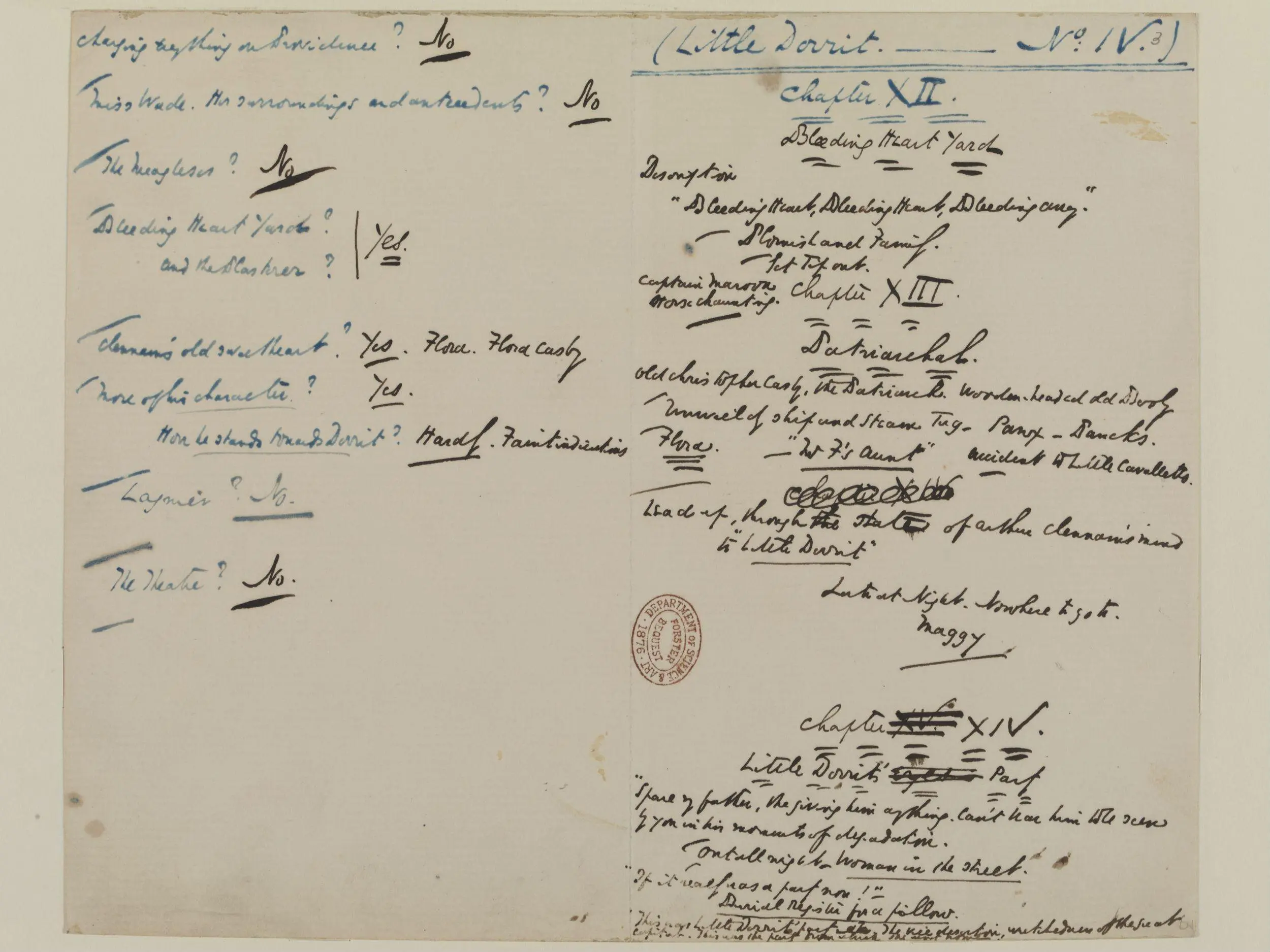

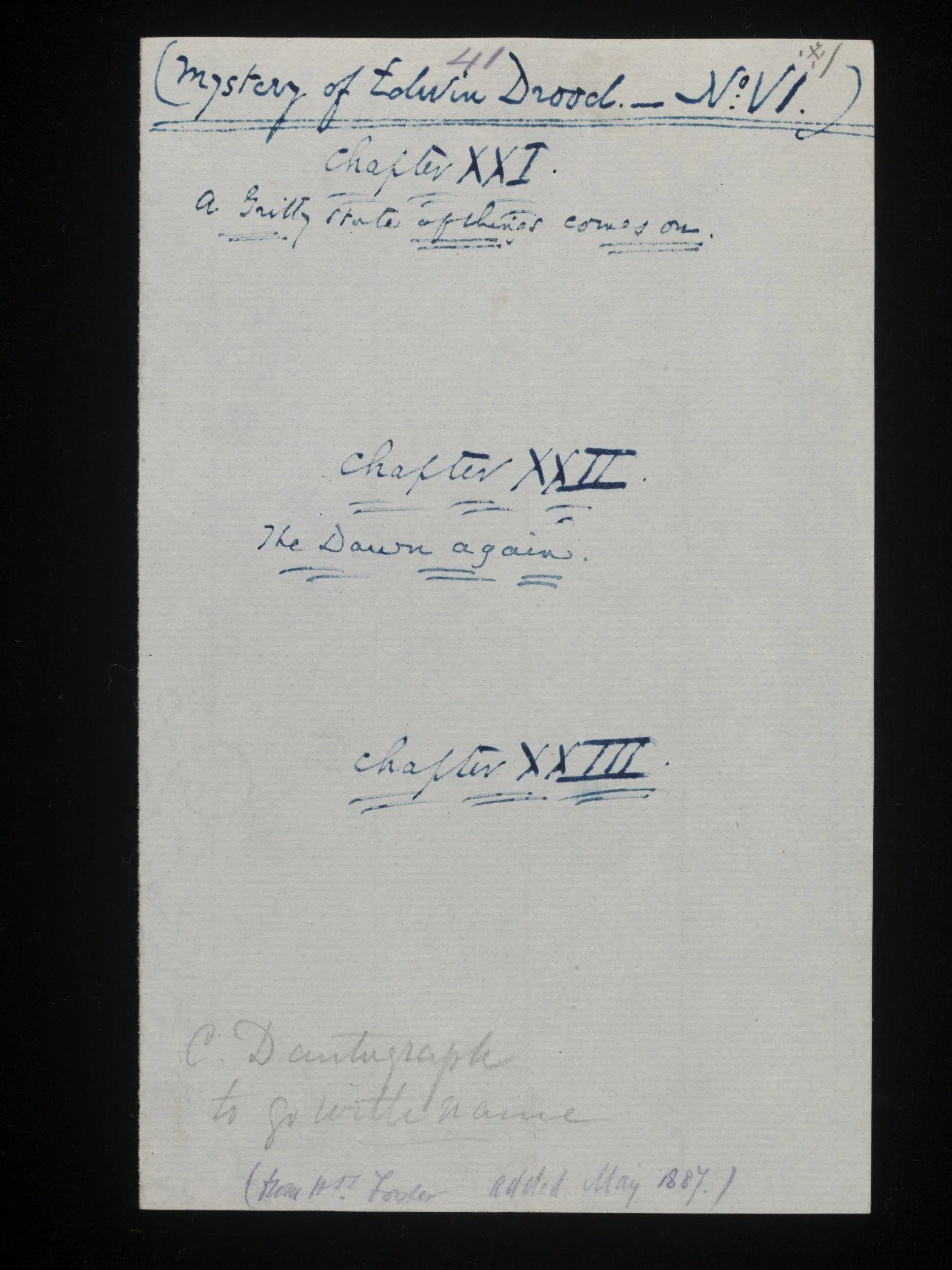

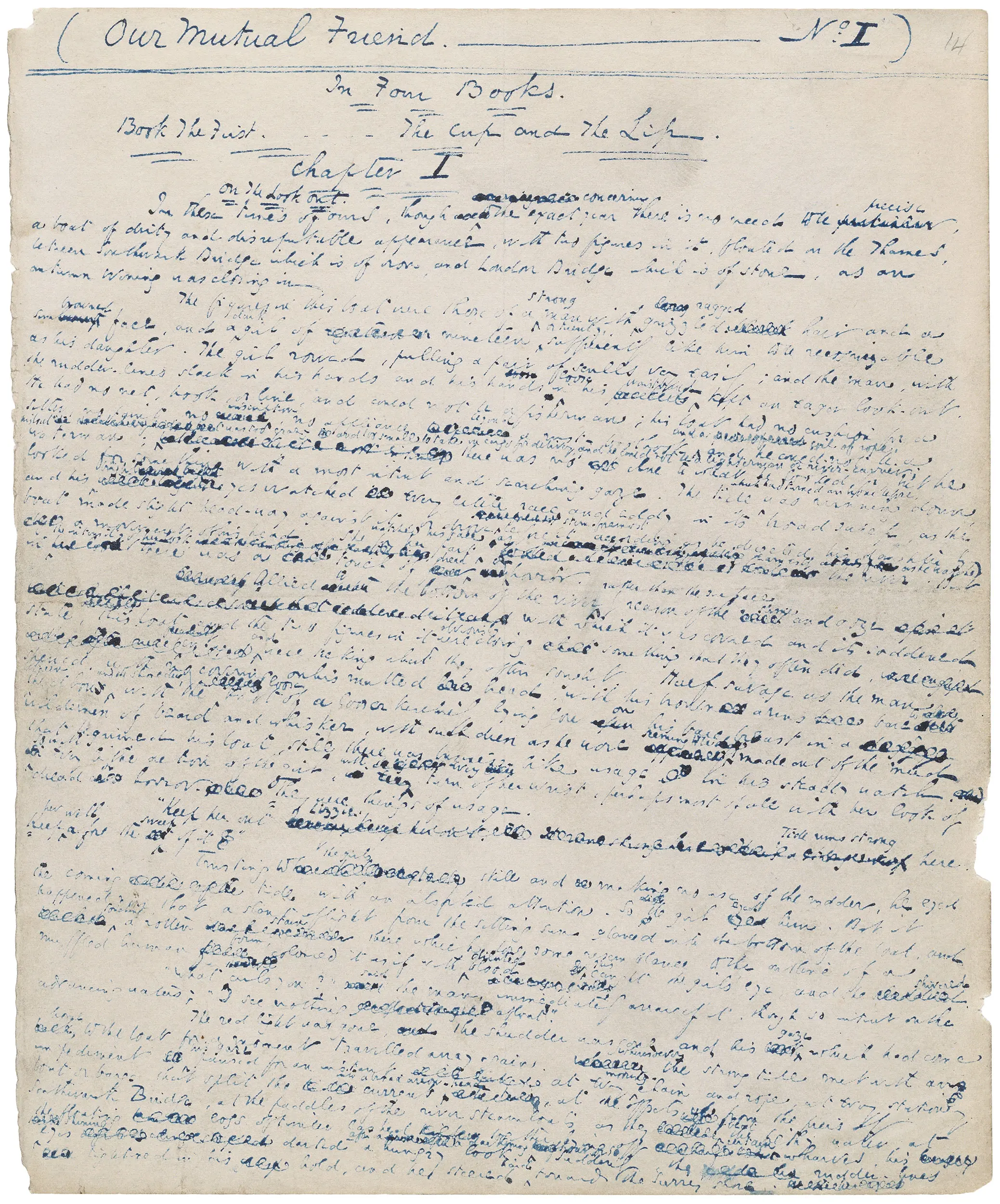

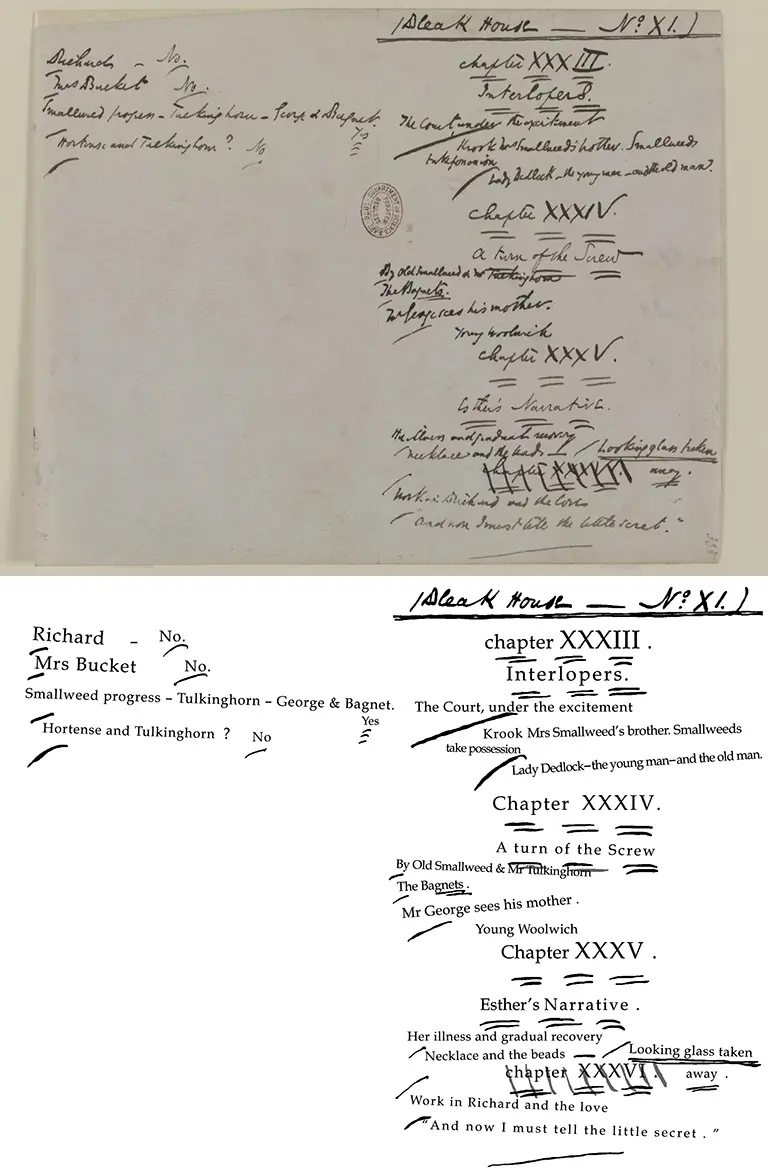

In most cases, Dickens would divide in half a 7” x 9” sheet of paper for each serial installment, folding a crease down the middle of the page. On the right side, he wrote the title and installment number and divided this side of the page into chapter numbers. From the evidence that survives from the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), we know that Dickens adopted the practice of creating a blank Working Note for each serial installment at the outset of a novel’s composition. He came back to fill in chapter titles and to jot down chief events and characters, occasional quotations, and memorable details. He used this space to test out names and phrases here and there, adding content over time, in some cases in cramped writing as space became short.

Dickens used the left side of the page for “generative” notes and memoranda for the installment as a whole, including long-term plans and motifs. Here we find questions about character combinations or plot details, often checked off or answered later in a different ink. At times he changes his mind. In some cases he uses this space to summarize work already completed or records his overwriting or underwriting of chapters and moves them around.

Complete sets of these Notes survive for all Dickens’s monthly novels following Dombey and Son, including David Copperfield (1849-50), Bleak House (1852-53), Little Dorrit (1855-57), Our Mutual Friend (1864-65), and the completed installments of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). Dickens also kept complete Notes for Hard Times (1854), which was published in weekly installments in Household Words. Planning documents and Notes also survive for The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41), Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44), and Great Expectations (1860-61), although they are not organized by installments.

Where are the Working Notes?

Dickens’s Working Notes are bound with his complete manuscripts in three libraries. The National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London holds the majority of Dickens’s manuscripts, which the author bequeathed to his friend and biographer, John Forster (1812-76) in his will. These are part of the library’s large Forster Collection, bequeathed to the museum upon Forster’s death in 1876. (See Lowe, “The Conservation of Charles Dickens’ Manuscripts”).1

The manuscript and Working Notes of Great Expectations are held at the Wisbech and Fenland Museum in Cambridgeshire, England. Dickens gave this manuscript to his friend Chauncy Hare Townshend (1798-1868), to whom he dedicated the novel. The two had been introduced by mesmerist John Elliotson in 1840. Townshend bequeathed the manuscript with additional materials to the Wisbech and Fenland Museum in 1868.

The Our Mutual Friend manuscript is held at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. Dickens presented this manuscript to Eneas Sweetland Dallas (1828-79) in January 1866 as a token of appreciation for Dallas’s favorable review of the novel in The Times (Nov. 25, 1865). The manuscript found its way from E.S. Dallas to George W. Childs in Philadelphia, who donated it to the Drexel Institute of Technology. It was subsequently purchased by the Morgan Library in October 1944.

The Digital Dickens Notes Project

While scholars have long recognized Dickens’s Working Notes as important resources for understanding the author’s writing process, their significance has been underappreciated. This is in part due to the difficulty of capturing their complex and dynamic relationship to Dickens’s compositional practices. Transcriptions of these Notes are often reproduced in the appendices to trade editions, but these black-and-white linear reproductions fail to capture the richness of these manuscripts: the size, color, and placement of elements on the page, as well as the non-textual markings Dickens used for emphasis and to record the process of his writing at various stages. The one complete facsimile version of the Working Notes, edited by Harry Stone and published by University of Chicago Press in 1987, captures considerably more detail alongside transcriptions, but this black-and-white edition is unwieldy in size and now out of print. Tony Laing’s open-access, online version of Dickens’s Working Notes for Dombey and Son provides color transcriptions and extended editorial commentary for Dickens’s first complete set of Working Notes.

The DDNP captures the materiality of the Working Notes in a digital space and provides editorial annotations to demonstrate how Dickens returned to these texts multiple times in the process of conceiving, composing, and editing each serial number of a long novel. Digital transcriptions offer legible versions of the Notes, while capturing the placement, size, and color, as well as non-textual markings as accurately as possible. Interactive annotations interpret the content of the Notes alongside the manuscripts, corrected proofs, and published texts of the novels, along with other records of Dickens’s compositional practice (letters, biographical accounts, etc.).

By facilitating an exploratory engagement with these texts as windows to Dickens’s serial writing, this project aims to open new avenues for interpreting Dickens’s approach to novel form. Rather than reading the Notes primarily as planning documents—records of preparation and design—as they have frequently been understood, we emphasize their role as dynamic records of serial process.

Read more about the DDNP’s approach to serial form and Dickens’s compositional practice, as well as our process for transcribing and annotating the notes, in the Scholarly Introduction.