David Copperfield Working Notes

Editor: Frankie Goodenough

Critical Introduction

How to cite:

Critical Introduction (MLA): Goodenough, Frankie. “David Copperfield Working Notes: Critical Introduction.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2023. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/david-copperfield/

The Working Note transcriptions for David Copperfield (MLA): Dickens, Charles. ”David Copperfield Working Notes,” transcribed and edited by Adam Grener and Frankie Goodenough. Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/david-copperfield/mirador/

Individual editorial annotations are written by Frankie Goodenough and can be cited by annotation number as displayed at the beginning of an annotation (e.g. DC.IX.R3).

Copperfield in Context

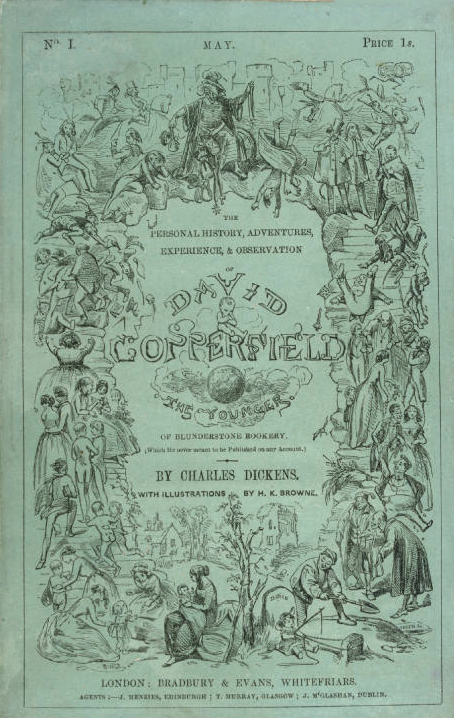

David Copperfield was published serially in twenty monthly parts by Bradbury & Evans from May 1849 to November 1850. Following Dombey and Son (1846-48), it is the second novel for which Dickens kept a complete set of Working Notes. These Notes, which are bound with the manuscript of the novel, were originally bequeathed to Dickens’s friend and later biographer John Forster, and are now kept in the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The only exception is the Working Note for the first installment, which was removed from the manuscript for use in Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens (1872-74); this sheet is bound with the Forster manuscript in the same library.

The DDNP’s annotations to the David Copperfield Working Notes explore Dickens’s varied use of the Working Note system throughout the nineteen-month period of the novel’s composition. In particular, we attend to Dickens’s tendency to use the Working Notes not as plans, but as retroactive records of the events and developments of installments that had already been written. Although this practice allowed for a more open and spontaneous approach throughout most of the novel’s composition, the last four Working Notes indicate Dickens’s adoption of a more rigorous and methodical approach to the final quarter of the novel in order to tie up its several narrative threads.

Titling the Novel: Copperfield ’s Genre and Form

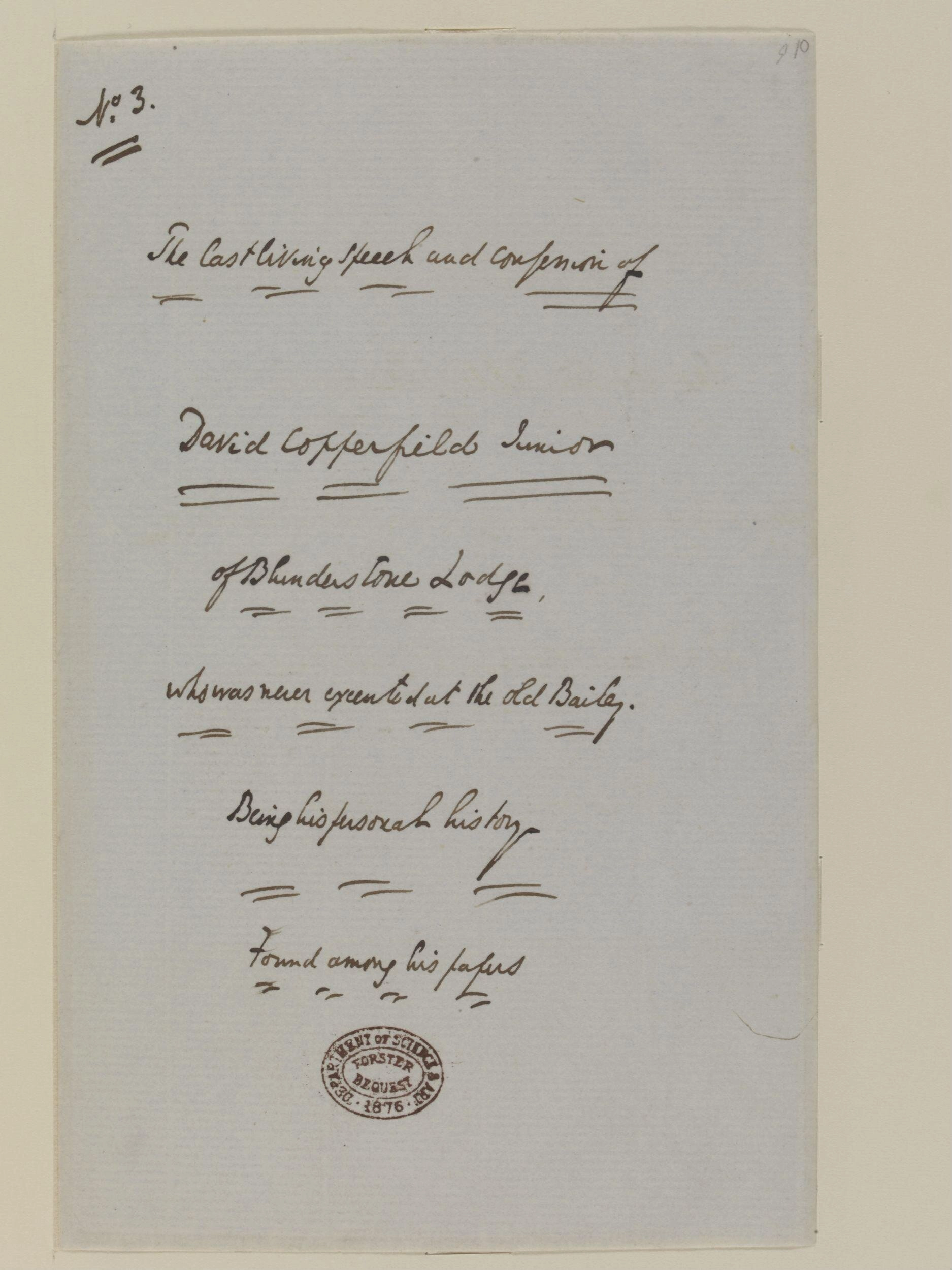

As he began “revolving a new work” in the early months of 1849 (Letters 5.489), Dickens wrote to Forster that he was experiencing the “deepest despondency […] in commencing” and selecting a name for his new novel (Forster 2.77). As he had done with Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44), and as he did again with Bleak House (1852-53), Dickens documented possible titles on several pages of notepaper that were later bound, along with the Working Notes, into the novel’s manuscript. The sixteen title sheets that accompany the Copperfield manuscript provide insight into a difficult titling process, and into Dickens’s changing attitude towards his eighth novel’s genre and narrative method in the early stages of composition.

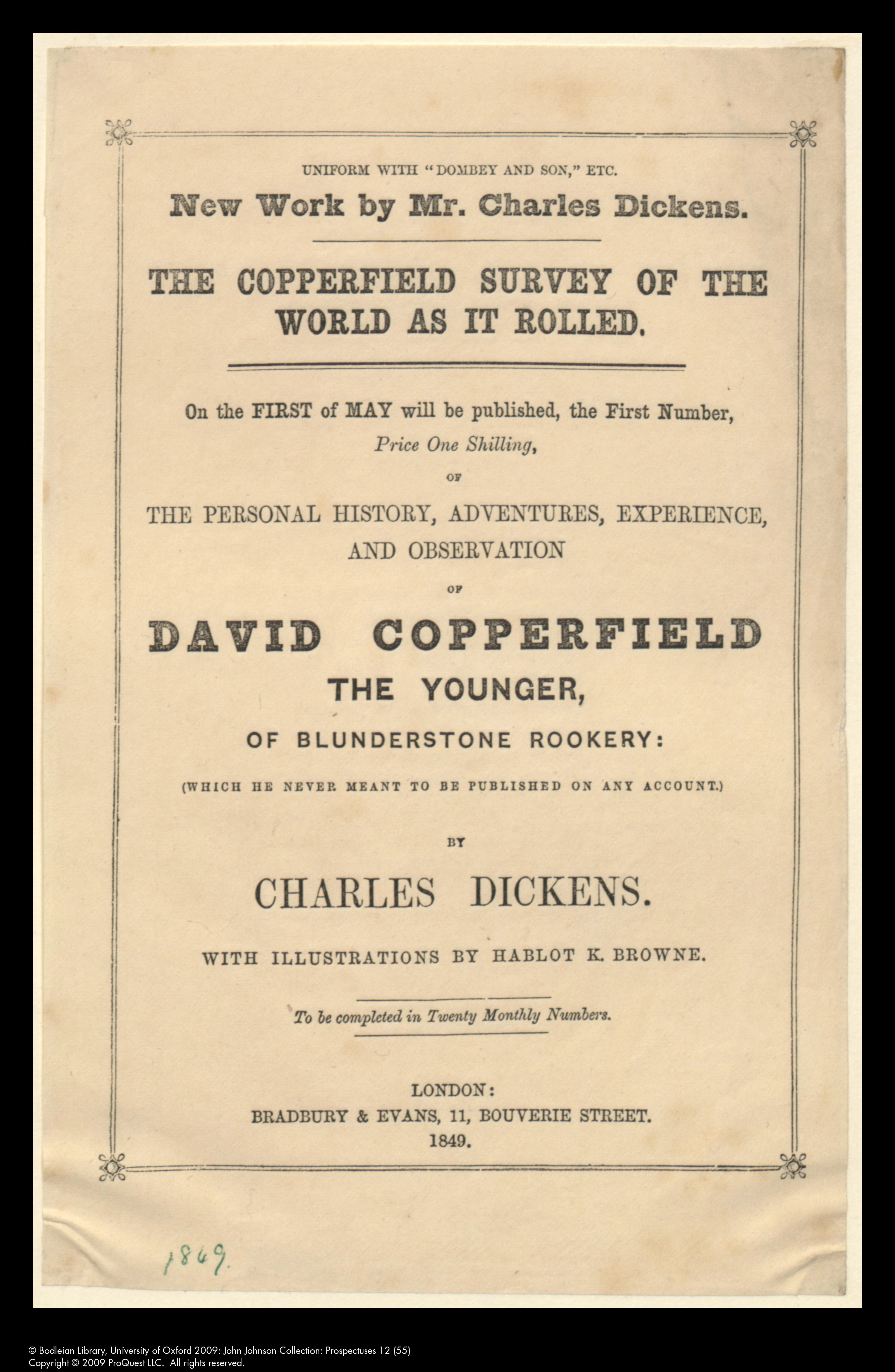

Dickens’s correspondence with Forster throughout February 1849 shows his progression through several different title concepts. The first of these was “Mag’s Diversions / Being the personal history, experiences, and observation of / Mr David Mag the Younger, / of Blunderstone House.” Another iteration of “Mag’s Diversions” retained the central motif, but identified itself as being a personal history of “Mr David Copperfield the Younger / And his Great-Aunt Margaret.” This idea was later replaced by a series of prototype titles that brought the biographical element of the novel more sharply into focus, including “The Copperfield Disclosures,” “The Last Will and Testament of Mr David Copperfield,” “Copperfield’s Entire,” “Copperfield, Complete,” and, ultimately, “The Copperfield Survey of the World as it Rolled.” The last of these titles pleased Dickens the most, and it became the novel’s working title as he embarked upon the first installment (Forster 2.78-79). An undated handbill (Dexter 159) and two advertisements published in The Examiner and the Athenaeum in April present the novel under this title first (Burgis xxv), followed by the name that the novel would ultimately be published under: The Personal History, Adventures, Experience, and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger of Blunderstone Rookery (Which He never meant to be Published on any Account). It was not until the second chapter had been drafted, according to Forster’s account, that Dickens had “defined to himself, more clearly than before, the character of the book,” and subsequently recognized the “propriety of rejecting everything not strictly personal from the name given to it” (Forster 2.79). Rather than a survey of the world, Copperfield was to be the narration of a life, and it is significant that even through the many iterations of the novel’s title, all sixteen trial title sheets feature the words “Personal History.”

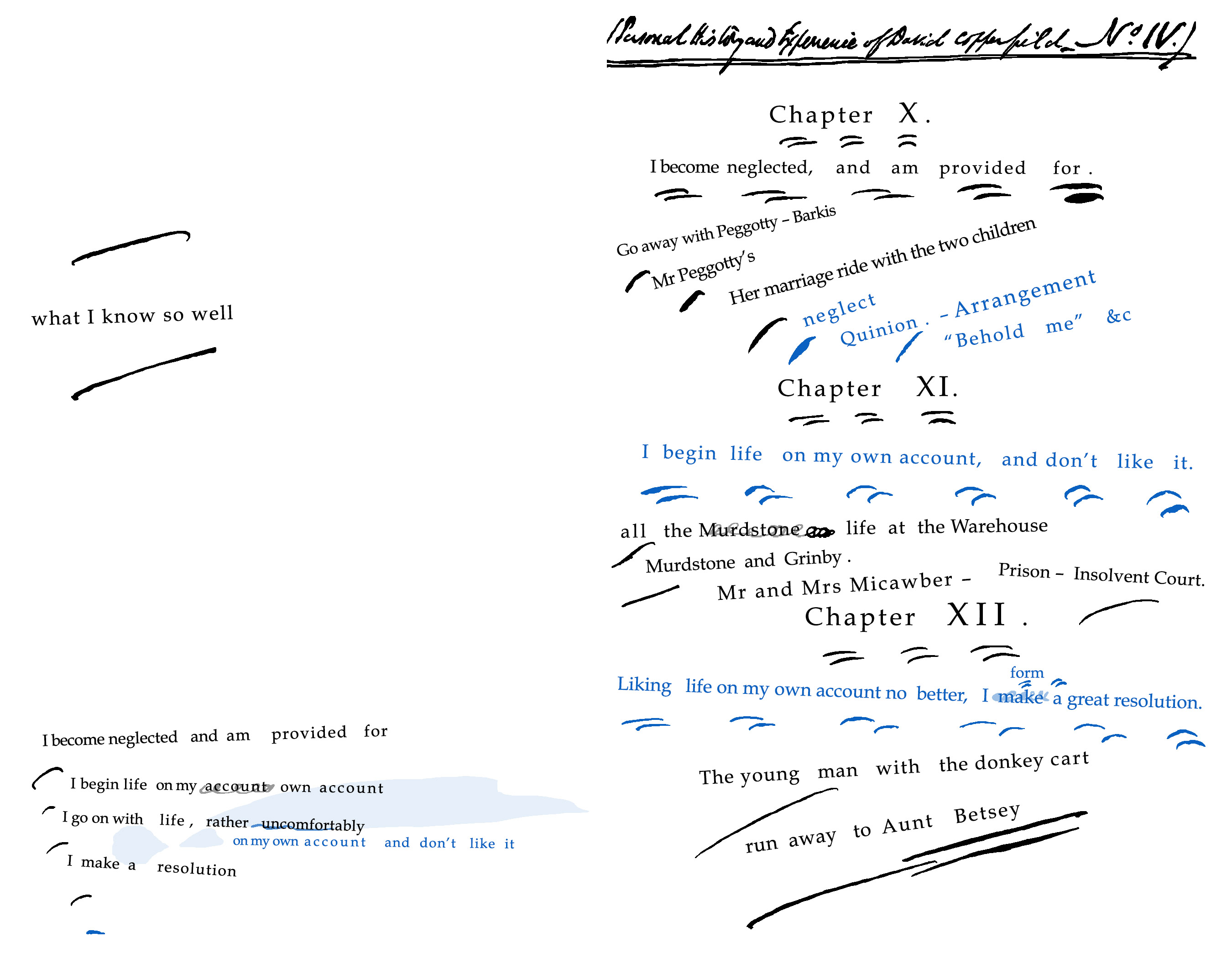

The idea of “Personal History” was to be kept at the forefront of the writer’s and the readers’ minds throughout the novel’s composition and serial publication. Its truncated title, which was used as a running header to the serial booklets, and was used by Dickens as a header for each number both in the manuscript and the Working Notes, was The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield. Initially Dickens had “Adventures” in place of “Experience,” but sometime after titling the Working Note for No. II, he changed his mind, and returned to the Working Note and manuscript to make the alteration (see DC_WN_02). This substitution suggests Dickens’s revision of his own early intentions for the novel. He had originally conceived of Copperfield as working in the tradition of Henry Fielding’s picaresque novels (in January he had named his son after Fielding as an “homage to the style of the novel he was about to write” [Letters 5.483]). While “Adventures” connotes the swashbuckling, episodic action of Fielding’s History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews (1742), History of Tom Jones (1749), and Dickens’s own Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39), David Copperfield’s emphasis on the “Experience” of a life comprehends its comparatively coherent structure and unity of purpose.

This unity was facilitated in part by Dickens’s use of the Working Notes system. Without the ability to refer to previous memoranda, to sketch out events several months in advance, or to experiment with various combinations of characters and events before and during the composition of a number, it seems unlikely that Dickens would have attained such thematic or narrative coherence over a nineteen-month compositional period. This is not to say that the Working Notes necessarily dampened the spontaneity of Dickens’s writing process; indeed, he frequently used the Working Notes as records for installments already completed, rather than blueprints for an installment yet-to-come. The Working Notes were an adaptable tool, and they furnished Dickens with a dynamic space that allowed him to balance the indeterminacy of the writing process with the control he felt was required by the “strong constraint[s]” of serial publication (Chuzzlewit 5).

“What I know so well”: Copperfield ’s Autobiographical Context

Forster describes the way that Dickens’s decision to write a novel in the first-person, initially suggested by Forster himself, ultimately brought about his resolution to draw on his own “early personal trials” in illustrating his protagonist’s childhood and youth (Forster 2.76). Copperfield is the most autobiographical of Dickens’s novels, and it is perhaps natural that his first foray into a first-person fictional narrative drew heavily on his own experiences. There are several general similarities between Dickens’s life and the life of his protagonist (for instance, David, like Dickens, works as a parliamentary reporter before becoming a celebrated author), but there are also several specific incidents in the earlier part of the novel that Dickens copied directly from an autobiographical fragment that he had written shortly before beginning Copperfield. Forster describes how Dickens, shortly after beginning the novel, “abandoned his first intention of writing his own life”; indeed, until the publication of Forster’s own account of Dickens’s boyhood (which reproduces the autobiographical fragment), David Copperfield was the only form in which these early experiences, still apparently “painful” to Dickens, were made public (1.19-20). He was especially pleased with his “complicated interweaving of truth and fiction” in No. IV, the novel’s most autobiographical installment (Letters 5.569), in which David goes to work at Murdstone & Grinby’s bottling factory—a fictionalization of the boot-blacking factory where the child Dickens began his “business life” (Forster 1.21). Several passages from No. IV are taken verbatim from the autobiographical fragment, like the passage in which David describes the painfulness of his situation in London (Copperfield 172; Forster 1.25):

That I suffered in secret, and that I suffered exquisitely, no one ever knew but I. How much I suffered, it is, as I have said already, utterly beyond my power to tell.

The annotations to the Working Notes discuss in greater detail the correlation between Dickens’s and David’s boyhood experiences. For example, David’s childhood reading material (Copperfield 66-67), his meals at the “famous alamode beef house” (171), his “magnificent order at the public house” (174), and his visits to the pawnbroker’s on the Micawber’s behalf (175-76), among other episodes, all find their source in Dickens’s autobiographical writing.

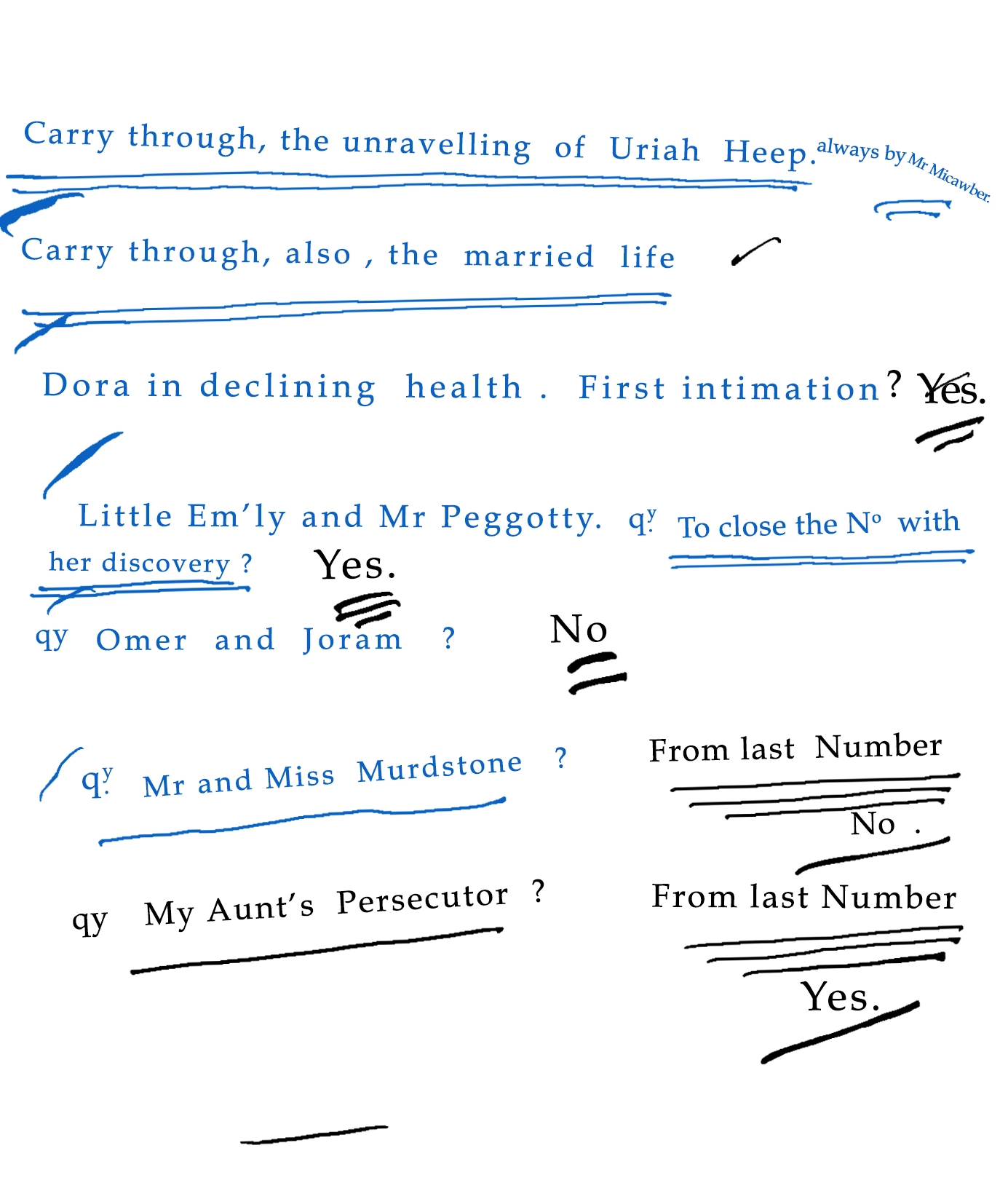

Given the close correspondence of life and fiction in the novel’s early installments, it is unsurprising that Dickens was in a position to write, on July 10, that he was “getting on like a house afire” with the fourth number (Letters 5.569). This success is also seen in the Working Note for that installment where, in place of the usual memoranda on the left-hand side, Dickens simply wrote, “What I know so well” (see DC.IV.L1). This is the only entry in the Copperfield Notes, and possibly in the entire corpus of Working Notes, where Dickens refers to himself using the personal pronoun. This striking entry demonstrates the way that the autobiographical elements of the novel challenge our ability to situate Dickens’s compositional practice, and his use of the Working Notes, within a linear narrative of artistic development. Since Copperfield is distinct among Dickens’s novels in its autobiographical aims, it follows that his compositional approach would also have been distinct. The Working Notes for David Copperfield are generally characterized by an emphasis on retroactive entries—notes and memoranda that Dickens added after writing an installment, rather than before. In comparison to the Working Notes for later novels, the Copperfield Notes place much less emphasis on explicit self-instruction and compulsive planning (in the Bleak House Working Notes, for example, it is more common to see Dickens remind himself to “carry on” with or “carry through” a line of plot, or “pave the way” for a particular event to occur in future installments). Although this might be partially accounted for by the nascence of the Working Note system, it must also be influenced to some extent by Dickens’s use of his own experiences in fashioning David’s personal history.

Retroactive to Proactive: The Working Notes for Copperfield

Forster wrote that Dickens “was probably never less harassed by interruptions or breaks in his invention” than when he wrote Copperfield (2.90), a claim which is supported by his retroactive additions to the Working Notes through much of the novel. We cannot be sure of the exact sequence in which “layers” of ink are applied to the Notes, the manuscript, and the corrected proofs; however, installments where Dickens changes ink or nib partway through composition (see, for example, DC.IV), along with examples where we see Dickens working through a particularly notable phrase during composition, allow us to speculate. The Working Note for No. XVI provides a helpful example: the “old ladies like birds” are documented on the Working Note, but the comparisons of Dora’s aunts to canaries are not added until the corrected proof stage, suggesting that the entries on the Working Note were added after Dickens composed and corrected the proofs of the chapter in question.

Yet while items on many of the Working Notes appear to have been added retroactively, the Notes for Nos. XVI-XX provide strong evidence for Dickens’s increasingly proactive approach in planning the novel’s final installments. In August 1850, while composing No. XVII, Dickens described the discipline that this late stage of composition required of him: “I have been very hard at work [at Copperfield] these three days […] Am eschewing all sorts of things that present themselves to my fancy—coming in such crowds!” (Forster 2.91). Though Dickens’s capacity for invention was apparently undimmed, these later Notes display increased restraint, indicating his preoccupation with the careful pacing of the novel’s climactic incidents and his desire to provide his serial readers satisfactory closure in the limited space that remained.

This increasing discipline is most clearly demonstrated by a number of proactive notes that Dickens appears to have written at the same time, in the same ink, across the left-hand sides of the final four Working Notes. These proactive memoranda were probably made sometime in late May or early June 1850, prior to the composition of No. XVI. They clearly refer to Dora’s illness and death, decided on or shortly after May 7th (Letters 6.94), but are written in the same dark blue ink used to compose Nos. XII-XV, rather than the black ink Dickens used for No. XVI. In these entries, Dickens anticipated and sketched out the major events still to come in the final four installments: the discovery (and recovery) of Emily, the escalation of Dora’s illness, the downfall of Uriah Heep, the storm at Yarmouth, the Peggottys’ immigration, David’s departure for Switzerland, and his union with Agnes. As he progressed through these final numbers Dickens added, responded to, and amended these original memoranda, producing a number of distinctly layered Working Notes. On the left-hand sides of the Notes for Nos. XVI-XVIII, Dickens also systematically jotted down items “from [the] last No.” that had been deferred, deciding at that point whether to include them in the current number or to defer them again to the following. Although he occasionally did this in earlier Notes, it was not done so regularly or methodically as in the final quarter of the novel. By setting up the Working Notes for Nos. XVI-XX in advance, Dickens ensured that he kept working steadily towards the conclusion of the novel, spreading the climactic events of the three major subplots across Nos. XVI-XVIII and enabling himself to tie up any remaining loose ends in the final double number.

The Working Notes for Copperfield are notable for their great variety. The transition from the sparsity of the Working Note for No. IV, to the compulsive planning of the Note for No. XVI, to the profusion of memoranda for the Note for No. XIX-XX, demonstrates the way that Dickens’s compositional practice adapted not only to the varying rhythms and pressures of serial publication, but also in response to the “natural progress and current” of a story that blended his own experiences with pure invention (Letters 5.677). Our annotations to the Working Notes explore the ways in which Dickens’s management of his story within the constraints of serial publication impacted the form of the published text. Rather than seeing the Copperfield Notes as defined by the novel’s place in Dickens’s career, we find that the dynamism of the Notes are indicative of the particular character of David Copperfield as a novel; they capture the fascinating tension that existed throughout Dickens’s career between active creative control and spontaneous invention during the course of serial composition.

Works Cited

- Bottum, Joseph. “The Gentleman’s True Name: David Copperfield and the Philosophy of Naming.” Nineteenth-Century Literature, vol. 49, no. 4, 1995, pp. 435-55.

- Burgis, Nina. “Introduction.” In David Copperfield, edited by Nina Burgis, Oxford UP, 1981, pp. xv-lxii.

- Butt, John, and Kathleen Tillotson. Dickens at Work. Methuen, (1957) 1968.

- Dexter, Watler, ed. The Dickensian, vol. 39, no. 268, 1943.

- Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield, edited by Nina Burgis. The Clarendon Dickens, Oxford UP, 1981.

- ——. David Copperfield, edited by Jeremy Tambling. Penguin, 2004.

- ——. The Letters of Charles Dickens: The Pilgrim Edition, 12 volumes, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson, Oxford UP, 1982-2002.

- ——. Martin Chuzzlewit, edited by Patricia Ingham. Penguin, 2004.

- ——. ”Pet Prisoners.” Household Words, vol. 1, no. 5, 27 April 1850, pp. 97-103.

- ——. Pictures from Italy, edited by Kate Flint. Penguin. 1998.

- Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, 2 volumes. JM Dent & Sons, (1872) 1927.

- Hawes, Donald. “David Copperfield’s Names.” The Dickensian, vol. 74, no. 385, 1978, pp. 80-87.

- Lettis, Richard. “The Names of David Copperfield.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 31, 2002, pp.67-86.

- Reed, John R. “Dickens and Naming.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 36, 2005, pp. 183-97.

- Siegel, Daniel. “Finding Form in David Copperfield: The Architectural Installment.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 48, no. 1, 2017, pp. 121-143.

- Stone, Harry. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.