Hard Times Working Notes

Editor: Adam Grener

Critical Introduction

How to cite:

Critical Introduction (MLA): Grener, Adam. “Hard Times Working Notes: Critical Introduction.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2023. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/hard-times/

The Working Note transcriptions for Hard Times (MLA): Dickens, Charles. ”Hard Times Working Notes,” transcribed and edited by Adam Grener and Isabel Parker. Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2023. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/hard-times/mirador/

Individual editorial annotations are written by Adam Grener and can be cited by annotation number as displayed at the beginning of an annotation (e.g. HT.III.L4).

The Origins of Hard Times

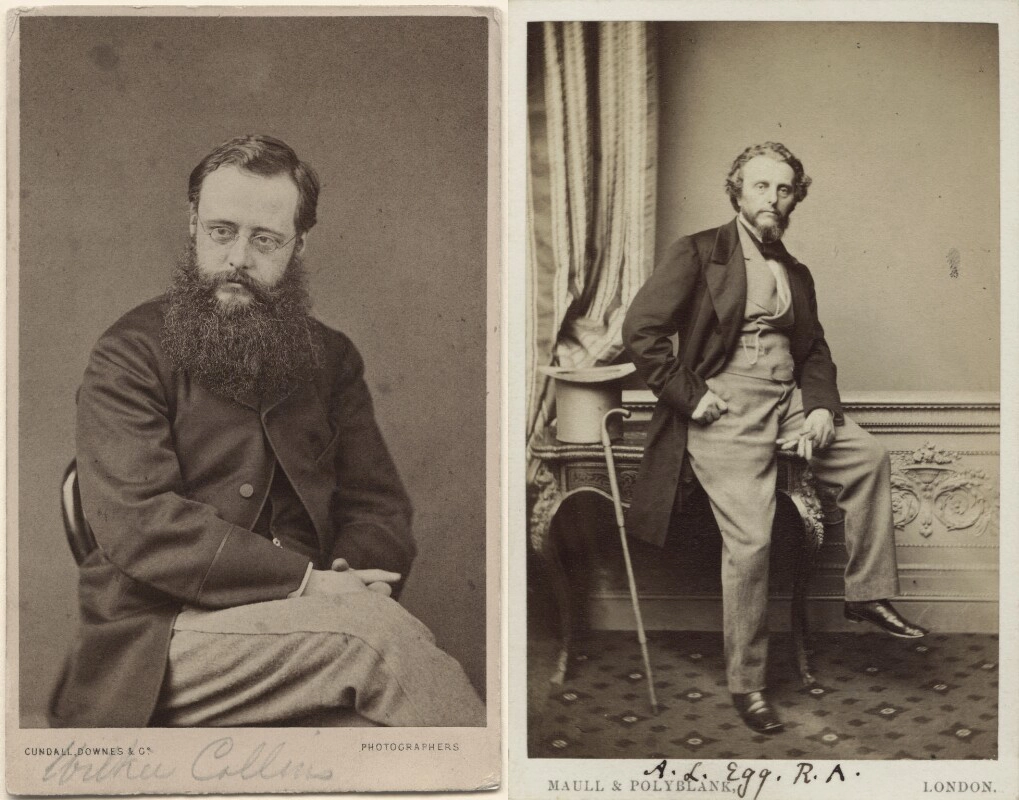

Dickens completed the composition of Bleak House in August 1853 (the final double number appeared in September) and had planned a respite from writing novels—“intend[ing] to do nothing in that way for a year,” as he would later write (Letters 7.453). In late September he wrote to John Forster: “I shall knock off; having had quite enough to do, small as it would have seemed to me at any other time, since I finished Bleak House” (Letters 7.157). In addition to ‘conducting’ Household Words, he had also just completed A Child’s History of England—which appeared in the journal between January 1851 and December 1853—and was “trying to think of something” for the upcoming Christmas issue (this would eventually become “Nobody’s Story”). Dickens “knock[ed] off” on a holiday tour of Italy with budding novelist and friend Wilkie Collins (1824-1889) and the painter Augustus Egg (1816-1863). The trio set off on October 10th, traveling first to Paris; then through Switzerland over the Alps by way of Lausanne, Geneva, and Chamounix; and onto Milan, where they arrived on the 24th. While this journey over the Alps would occupy Dickens’s imagination as Little Dorrit (1855-57) began to take shape in the following year, the present itinerary included stops in Genoa, Naples, Rome, Florence, Naples, and Turin, before the group returned by way of Paris.

Returning to London in mid-December to prepare for a series of Christmas readings in Birmingham, Dickens was confronted with “plummeting circulation figures” of Household Words, whose profits had halved through 1853 (Slater 365). Dickens had necessarily been less involved in the day-to-day handling of the journal while abroad, and had provided his sub-editor W.H. Wills the “Conductorial Injunction” to “KEEP ‘HOUSEHOLD WORDS’ IMAGINATIVE!” when writing from Rome in November (Letters 7.200). But the declining sales began well before his travels, and by the end of the year his publishers Bradbury & Evans and journal co-partners Forster and Wills had convinced him that a new novel published in weekly installments would be the best way to correct the fortunes of Household Words. Accordingly, a publication agreement dated December 28th was drawn up between the parties, engaging Dickens to write “at his earliest convenience” a story “equal in length to five single monthly numbers of Bleak House” (Letters 7.911). The agreement is explicit about being made “with a view to the enlargement of the circulation of Household Words and the consequent enhancement of the value of their several shares.”

Dickens had made a similar intervention while editing Master Humphrey’s Clock in 1840 by writing The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41), and would do so again later to boost sales of All The Year Round with Great Expectations (1860-1861). These situations differed, however, in that Dickens had already created or conceived of the principle characters for these works and so could build from there (Slater 366). Hard Times also differs from these novels in that, while provisional notes and memoranda survive for The Old Curiosity Shop and Great Expectations, Hard Times is Dickens’s only weekly serial for which he kept complete Working Notes.

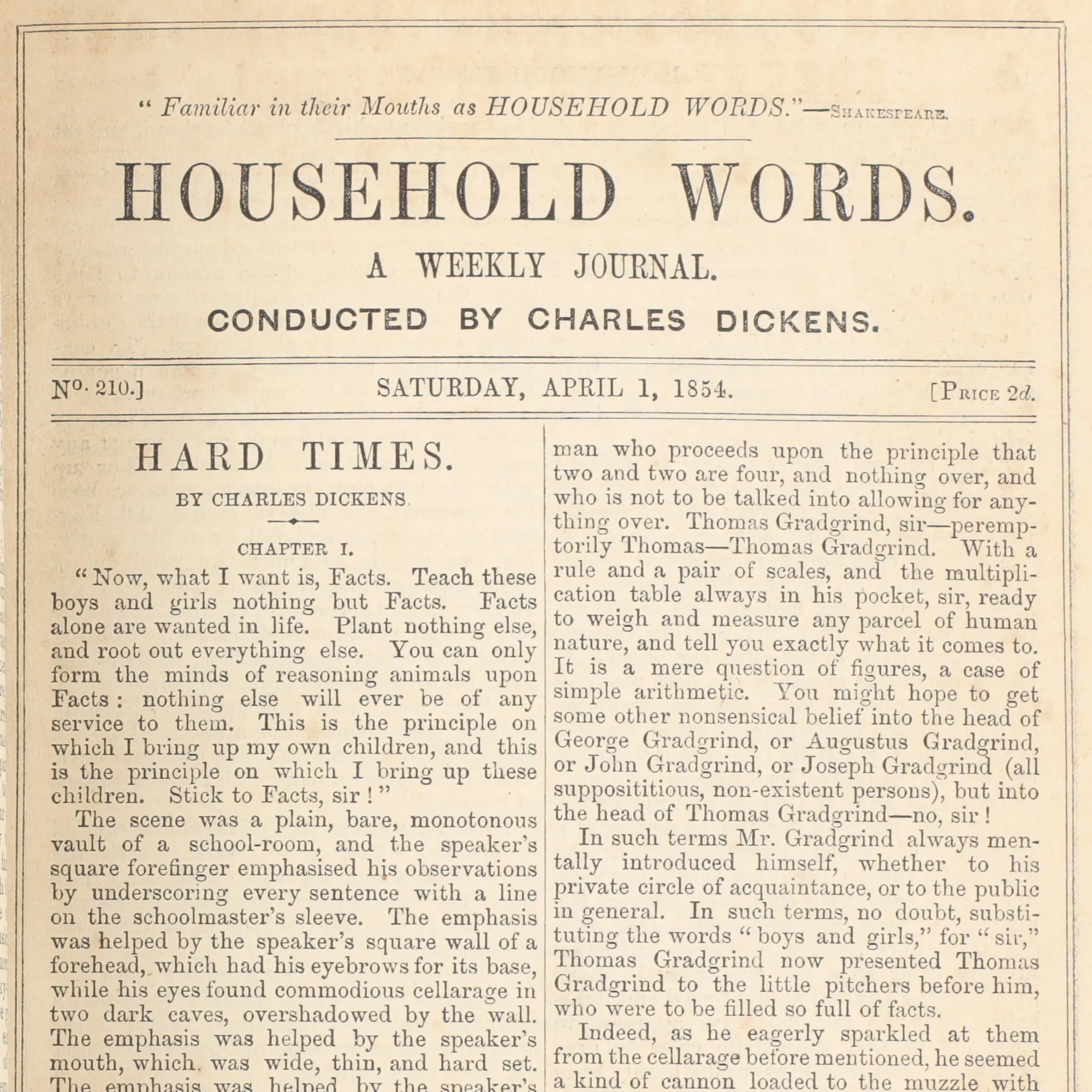

The Notes begin with two half-sheets, both dated January 20, 1854. On one, he generated a list of possible titles for his new novel; on the other, he calculated, using Bleak House as a basis, the quantity of manuscript pages needed to fill the allotted weekly columns in Household Words. On the same day, he sent fourteen titles from this list to Forster, remarking that “it seems to me that there are three very good ones among them” and wondering “whether you hit upon the same [three]” (Letters 7.254). Hard Times was chosen as the title because it was the only one selected by both (Forster 2.120). Transcriptions of these two sheets accompany our transcriptions of the five Working Notes, with annotations that explain and further explore their significance (see HT_WN_Mems). By March 9th Dickens was writing to Emile de la Rue that “I did intend to be as lazy as I could be all through the summer, but here I am with my armour on again” (Letters 7.288); the first installment of Hard Times appeared in due course in issue no. 210 of Household Words, dated Saturday, April 1, 1854, with the journal’s income recovering as hoped during its serial run.1

“I have no intention of striking”: Hard Times and the Industrial Novel

In its content and composition, Hard Times reflects the ambivalence about industrialism that runs through Dickens’s novels (see Brantlinger). As early as 1838 he had considered “strik[ing] the heaviest blow” (Letters 1.484) against the factory system and the conditions of child laborers following his tour of Manchester and Birmingham. Yet aside from Little Nell’s nightmarish journey through the industrial north in The Old Curiosity Shop, he had not taken up the issue directly. If Dickens’s turn to the industrial novel at this moment can be regarded as belated in terms of the genre’s history (see Joshi), its concerns were still legibly topical. Dickens was in fact in Birmingham for his series of Christmas readings when the publication agreement with Bradbury & Evans was signed. The third and final of these readings on December 30th was designated a “Working-people’s night” (Letters 7.244) at Dickens’s request, and discounted tickets attracted a rapt audience of over two thousand workers. Dickens prefaced his reading of A Christmas Carol with a speech that emphasized “the bringing together of employers and employed” and “the creating of a better common understanding among those whose interests are identical, who depend upon each other, and who can never be in unnatural antagonism without deplorable results” (Speeches 167).

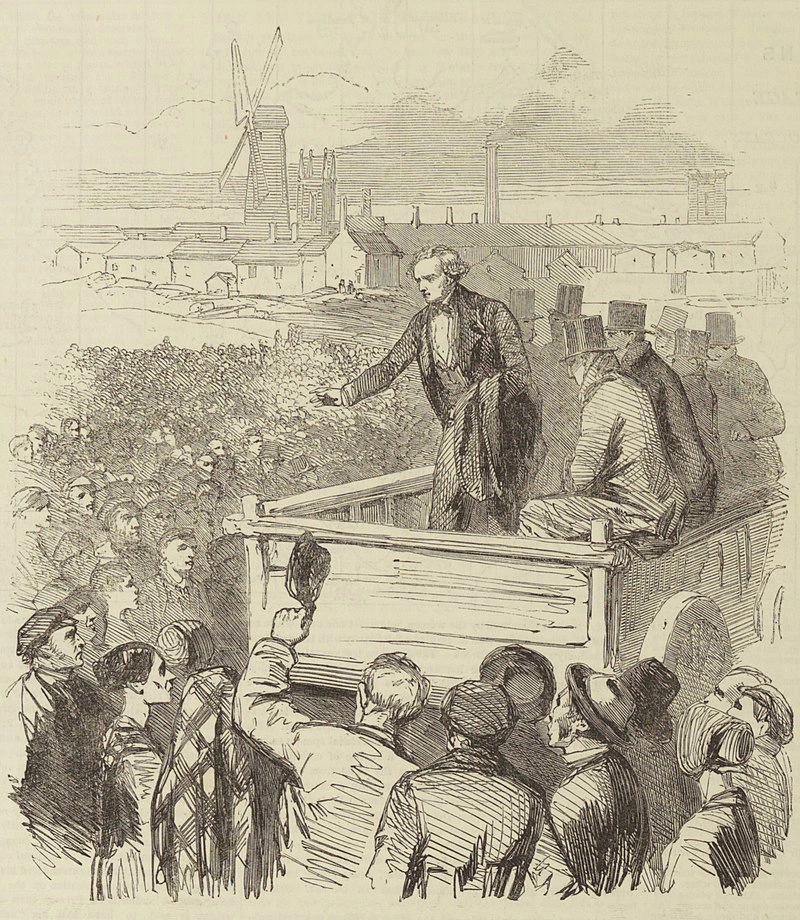

Dickens’s call for greater understanding between “men and masters” was made against the backdrop of protracted labor unrest further north in the Lancashire town of Preston. In October 1853, mill owners had locked out weavers who had been striking since August in support of a ten-percent increase in wages, and Dickens had read news of the “unhappy strikes” from Italy in November (Letters 7.213). In late January 1854—within a week of commencing work on Hard Times—he set out with Wills to observe the ongoing situation first-hand. The immediate consequence was an article, “On Strike,” which Dickens penned for the February 11th issue of Household Words. The article is an “impressionistic piece of reportage, concerned to reassure his middle-class readers” that the strike was no revolutionary force (Slater 370). At one point, it depicts the labor delegates’ discussion being interrupted by a fiery speech from “Gruffshaw,” a portrait of the activist leader Mortimer Grimshaw. Dickens would later revisit these scenes in Hard Times through the “Popular leader” Slackbridge (see HT.III.L4). “On Strike” also concludes by describing the “strike and lock-out” as a “deplorable calamity” that becomes “a great national affliction” through “the gulf of separation it hourly deepens between those whose interests must be understood to be identical or must be destroyed” (558).

Although Hard Times is clearly drawing from and responding to these events, Dickens’s creation of Coketown is far more than a simple fictional rendering of Preston. Following his visit, he wrote to Forster: “I am afraid I shall not be able to get much here,” since aside from “the cold absence of smoke from the mill-chimneys, there is very little in the streets to make the town remarkable” (Letters 7.260). In early March, Dickens wrote privately to Peter Cunningham in response to an article in The Illustrated London News in which Cunningham claimed that Dickens’s visit to Preston had “originated the title” and “suggested the turn of the story” of the forthcoming novel (Letters 7.290fn3). Dickens may have been exaggerating slightly when he told Cunningham that “the title was many weeks old, and chapters of the story were written, before I went to Preston” (7.290). Nevertheless, Dickens’s fear that Cunningham’s “pernicious” claim would lead readers to “localiz[e]” a story “which has a direct purpose in reference to the working people all over England” reveals his sensitivity to the peculiar coupling of fact and fiction in the pages of Household Words.

It appears that Dickens had decided relatively early on to distance his novel from the specifics of labor unrest and to instead focus more generally on the critique of political economy. By late April, Dickens was corresponding with Elizabeth Gaskell about the publication of her new novel North and South (1854-55), which would appear in Household Words following the serial run of Hard Times. Having seen the early parts of both novels, Forster grasped the potential conflict in their shared concern with “manufacturing discontents,” and he wrote to Gaskell to say that “I know nothing yet from [Dickens] as to how far he means to use that sort of material. Nor do I think he knows himself” (Letters 7.320fn7). Dickens followed up with Gaskell a few days later to reassure her (7.320):

I have no intention of striking. The monstrous claims at domination made by a certain class of manufacturers, and the extent to which the way is made easy for working men to slide down into discontent under such hands, are within my scheme; but I am not going to strike. So don’t be afraid of me.

Unlike Gaskell’s novel, Hard Times ultimately offers only brief glimpses into the personal lives of mill workers, perhaps due to the compressed space of the novel. Instead Dickens uses the novel’s industrial setting to forcefully dramatize the point he would make at the conclusion of “On Strike”: that “political economy is a mere skeleton unless it has a little human covering and filling out, a little human bloom upon it, and little human warmth in it” (558).

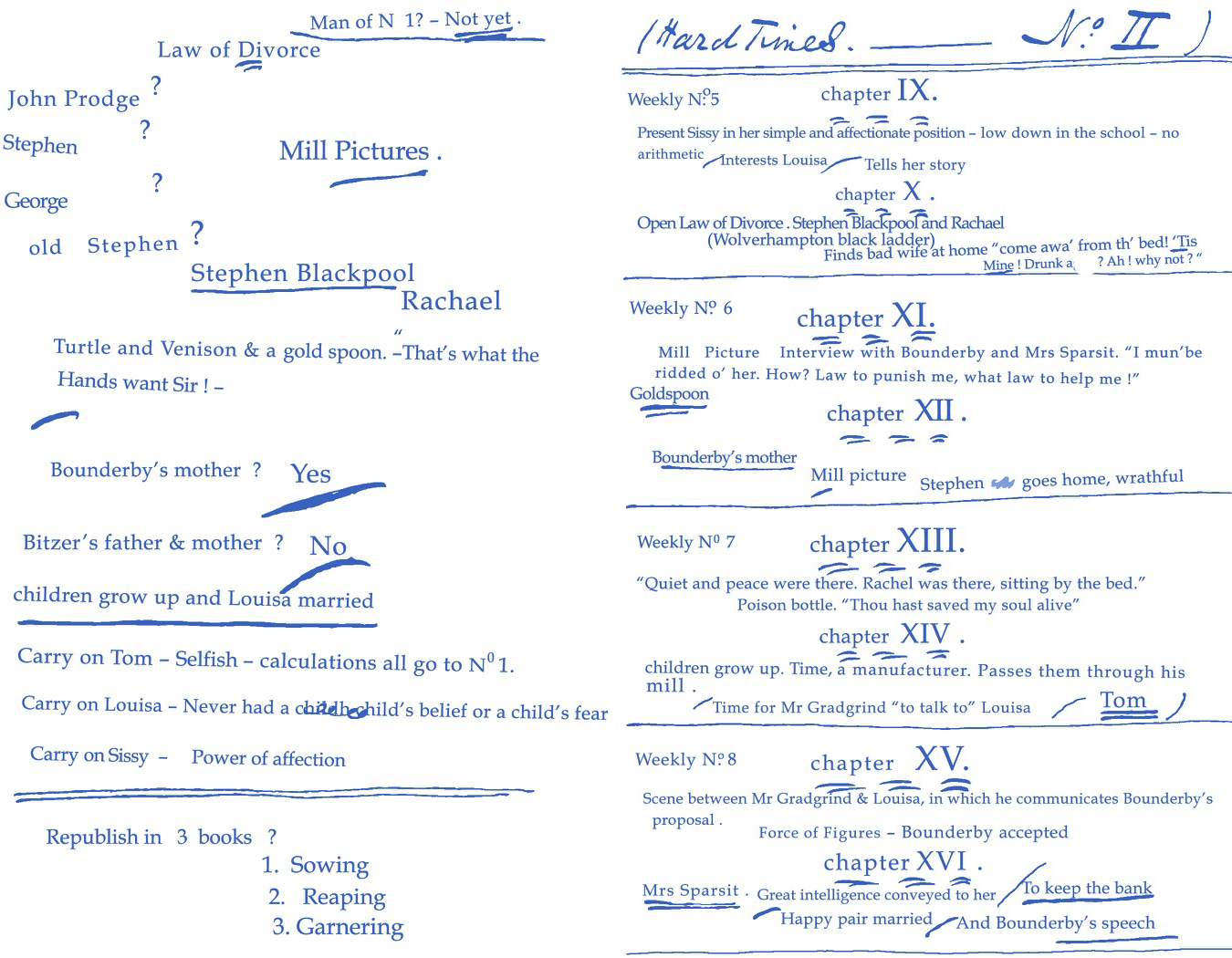

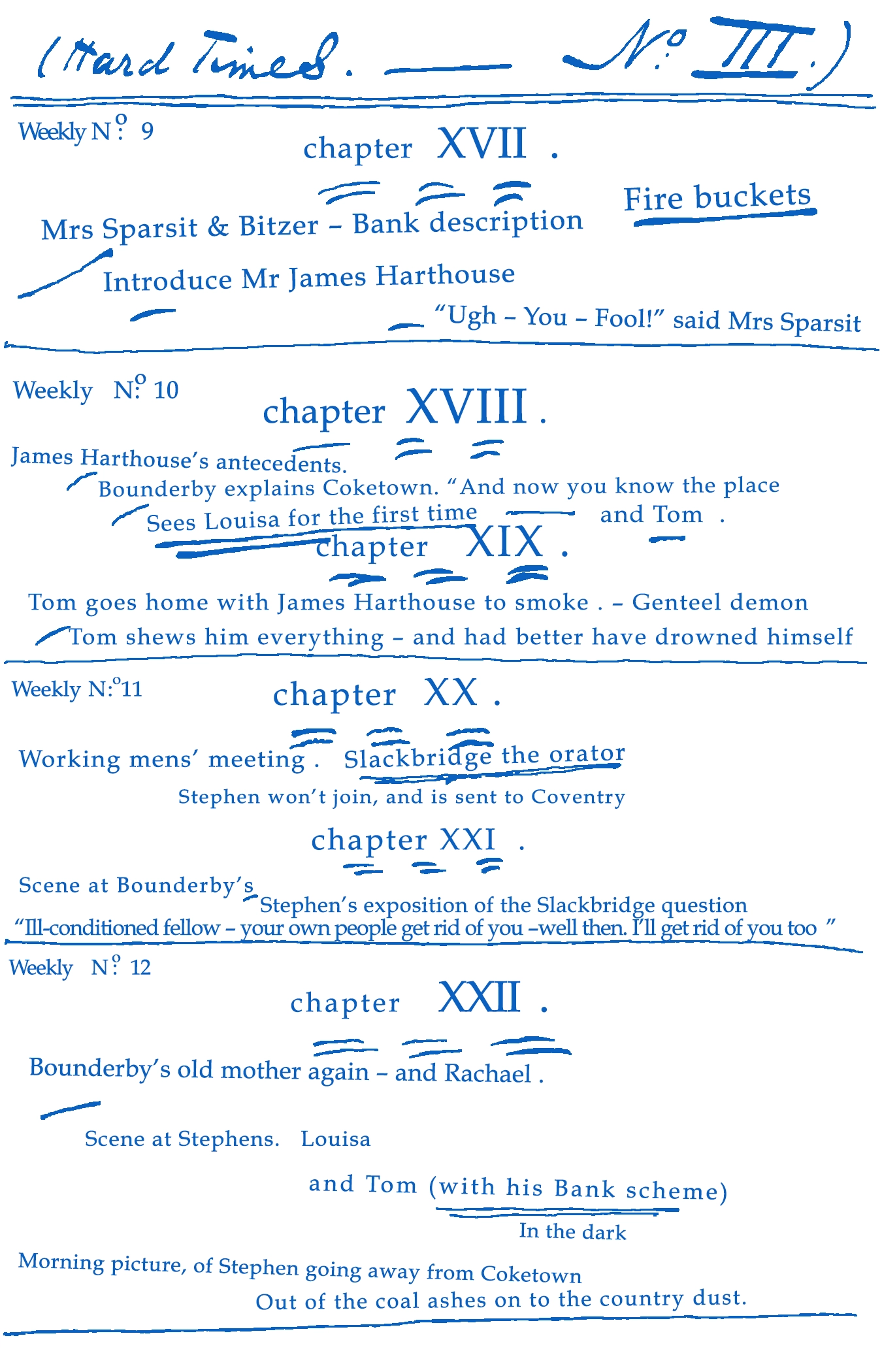

“The difficulty of the space is CRUSHING”: Calculating the Weekly Serial

The publication agreement with Bradbury & Evans specified that Dickens’s new novel would be “equal in length to five single monthly numbers of Bleak House” and would appear “in continuous weekly portions” (Letters 7.911). However, it left the length of each weekly installment to be determined “as Mr. Dickens, in his Capacity, as Editor, may think fit.” It made sense for Dickens—as both author of Hard Times and editor of Household Words—to publish the novel in roughly equal portions each week. The Working Note system must also have been a significant factor in this decision to simply carry over the accustomed length of the monthly number and divide it into four weekly portions. As the leading left-hand memoranda on the first Working Note shows, Dickens decided to “Write and calculate the story in the old monthly N[umbers]” (see HT.I.L1). The Working Note system—which Dickens had established writing Dombey and Son (1846-48) and carried through the writing of David Copperfield (1849-50) and Bleak House (1853-54)—provided a systematic way to “write and calculate” this new novel, even though its publication format differed. The five Working Notes Dickens generated for Hard Times show him trying to compose this new novel in the temporal rhythms and parameters of the monthly number.

Yet composing a monthly number that was then to be further subdivided proved difficult from the outset. As early as February Dickens complained to Forster (Letters 7.282):

The difficulty of the space is CRUSHING. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room always, and open places in perspective. In this form, with any kind of regard to the current number, there is absolutely no such thing.

As the Working Notes for Copperfield and Bleak House illustrate, Dickens typically began each monthly number by dividing it into three chapters, adding a fourth if circumstances required. It is not just that each ‘number’ of Hard Times had to be four, roughly equal weekly portions, but also that each of those portions had to stand on its own—to advance the plot, to develop characters and themes, and to carry readers through to the next installment. On the first Working Note Dickens appears to have retroactively recorded the division of the ‘number’ into its four weekly installments. However, on the remaining four Notes he uses lines to subdivide the right-hand side of the Note into four portions from the outset of planning, and the memoranda he subsequently records are often ‘crushed’ into the diminished space of the weekly installment.

Dickens appears never to have adequately resolved these issues with space while writing Hard Times. His letters to Wills during this period—typically a mixture of Household Words business and personal exchange—document a consistent frustration with the creative demands of the format. In April, Dickens writes that he is “in a dreary state, planning and planning the story of Hard Times (out of materials for I don’t know how long a story), and consequently writing little” (Letters 7.317). In early May, he reports he is “Growling in a general way” (7.328). And writing from Boulogne where he had retreated in July to finish the novel, Dickens complains that he is “addled by Hard Times” and “very much in need of rest. Head very hot. Sometimes nervous” (7.365). As he looked forward to completing the final monthly ‘number,’ issues of space came to a head, and each weekly portion was “enlarged to 10 of my sides each—about” (see HT.V-VI.L1). The novel threatened to spill over into an extra, twenty-first installment, but its final three chapters ultimately appeared together, taking up nearly half of the August 12th issue of Household Words. Writing to Lavinia Watson in November 1854, Dickens confided that Hard Times had left him “tired!” and “‘used up,’” “perhaps because […] the compression and close condensation necessary for that disjointed form of publication, gave me perpetual trouble” (7.453).

The Working Notes for Hard Times

Dickens would later write two more novels published in weekly installments—A Tale of Two Cities (1859) and Great Expectations—but did not utilize the Working Note system for either. While his rationale for this remains unknowable, the Working Notes for Hard Times ultimately provide a unique glimpse into Dickens’s compositional process as he navigated the specific demands of the weekly serial. Our transcriptions of the Notes include the two preliminary half-sheets and the five Notes where he conceptualized and documented the five ‘numbers’ of the novel. Throughout our annotations, we make reference to these ‘numbers,’ even though this architecture was only visible to Dickens himself (and perhaps his partners in Household Words). Although modern readers encounter the novel as divided into three “books” (“Sowing,” “Reaping,” & “Garnering”), these divisions were only conceived by Dickens during composition of the novel and imposed when the novel was re-published in book format later in 1854 (see HT.II.L8). It is at this time that Dickens also expanded the title to Hard Times for These Times, added titles to the chapters, and included the dedication to Thomas Carlyle.

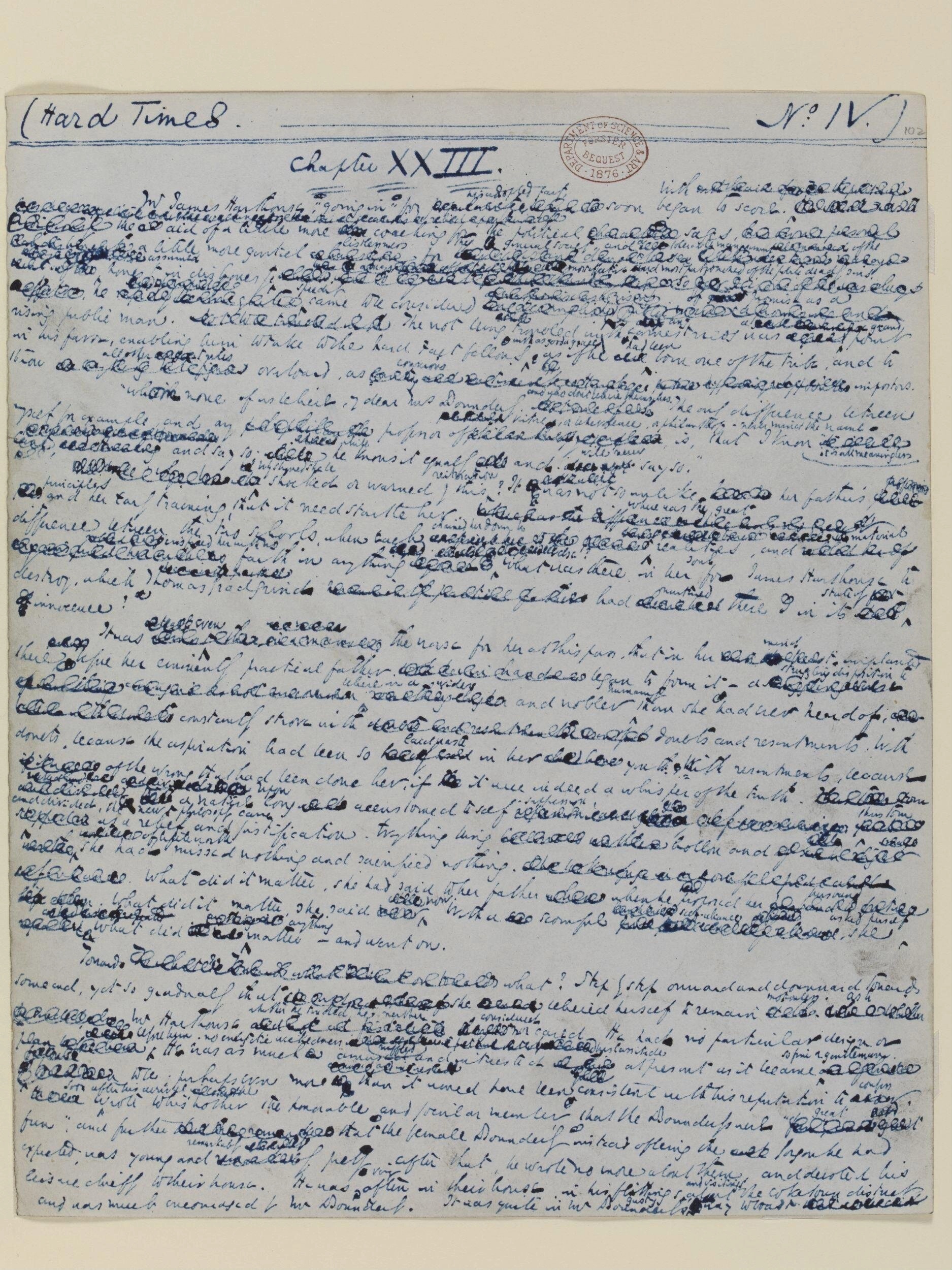

The entirety of the manuscript and Working Notes for the novel appear in blue ink, so the definitive transitions between ink colors that make some of the temporal layers on the Notes clearly legible are not present. Nevertheless, distinct differences in the appearance of Dickens’s handwriting (produced, for example, by a different nib or even shade of blue ink) confirm that each Working Note for Hard Times is the product of multiple, distinct engagements before, during, and after composition of each ‘number.’ Some of our annotations describe these differences and speculate on their relationship to the temporal composition of the Note and novel.

Although Dickens’s reasons for adopting the monthly format in the planning and composition of Hard Times have been described as “half-technical, half-sentimental” (Ford 231), the decision had significant artistic implications. Most notably, decisions made during the course of conceiving and writing each of the five ‘numbers’ shaped how material was excluded or deferred within these larger units. For example, although Dickens had conceived the character who was to become James Harthouse and described him on the Working Note for No. I, his appearance is deferred. This “Man of N[umber] 1” is carried over to the Note for No. II, where once again his introduction is deferred (see HT.II.L1). It is only on the Working Note for No. III where this “Man dropped in N[umber] 1” is given a name and role in the narrative (see HT.III.L3). This same Note ponders expanded possibilities for Sissy Jupe—either to have a “lover” or “to be acquainted” with Rachael—but Dickens’s navigation of these possibilities within the constraints of this ‘number’ (in this case, rejecting them) has ramifications for the remainder of the novel. Therefore, while critics from the mid-twentieth century onward have tended to emphasize how the compressed format of the novel furthers its purpose as a “moral fable” (Leavis 250; see also Humphreys, Slater pp. 368-369), the Working Notes also map the tensions between part and whole that define Dickens’s novelistic craft and energize the Working Note system through his career.

Works Cited

- Baird, John D. “‘Divorce and Matrimonial Causes: An Aspect of ‘Hard Times.’” Victorian Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, 1977, pp. 401-412.

- Brantlinger, Patrick. “Dickens and the Factories.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 26, no. 3, 1971, pp. 270-285.

- Butt, John, and Kathleen Tillotson. Dickens at Work. Methuen, (1957) 1968.

- Dickens, Charles. Hard Times, edited by David Craig. Penguin, 1987.

- ——. “Fire and Snow.” Household Words, vol. 8, no. 200, 1854, pp. 481-483.

- ——. The Letters of Charles Dickens: The Pilgrim Edition, 12 volumes, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson, Oxford UP, 1982-2002.

- ——. “On Strike.” Household Words, vol. 8, no. 203, 1854, pp. 553-559.

- ——. The Speeches of Charles Dickens, edited by K.J. Fielding, Oxford UP, 1960.

- Fielding, K.J. “Charles Dickens and the Department of Practical Art.” Modern Language Review, vol. 48, no. 3, 1953, pp. 270-277.

- Ford, George and Sylvère Monod. “Dickens’ Working Plans” & “Textual Notes,” in Hard Times, edited by George Ford & Sylvère Mondon, W.W Norton & Company, 1966, pp. 231-270.

- Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, 2 volumes. JM Dent & Sons, (1872) 1927.

- Grose, Francis. 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: A Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit, and Pickpocket Eloquence. Macmillan Publishers Ltd., (1811) 1981.

- Hager, Kelly. Dickens and the Rise of Divorce: The Failed-Marriage Plot and the Novel Tradition. Routledge, 2010.

- Humpherys, Anne. “Hard Times,” in A Companion to Charles Dickens, edited by David Paroissien. Blackwell Publishing, 2008, pp. 390-400.

- Joshi, Priti. “An Old Dog Enters the Fray; or, Reading Hard Times as an Industrial Novel,” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 44, 2013, pp. 221-241.

- Leavis, F.R. The Great Tradition. Penguin Books, (1948) 1966.

- Morley, Henry. “Ground in the Mill.” Household Words, vol. 9, no. 213, 1854, pp. 224-227.

- Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers, 2nd ed. Oxford UP, (1978) 2017.

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. Yale UP, 2009.

- Stone, Harry. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Footnotes

-

Income for the journal had risen to £1303 for the half-year ending 30 March 1853, the highest it would ever reach (Patten 412). During the following half-year it fell to £528, and through the following period ending 30 March 1854 it fell even further to £393. Between 1 April 1854 (when Hard Times commenced) and 30 September, income had recovered to £933. ↩